This is my final issue of this newsletter in 2024. Thanks to everyone who read it this year. I’ll be back with a January monthly issue next year. Happy Holidays and Happy New Year to each of you.

Please consider joining me in the next couple of weeks to donate to a local abortion fund. Details about FUND ABORTION ACCESS in 2025 is here. You can donate here. My goal is to raise at least $50,000 for abortion funds by January 1. I am also looking for someone who is willing to create some social media graphics for this project.

Also, please consider making a year-end donation to support REBUILD. It’s the only program of its kind in the U.S. and I would love to see it continue its good work.

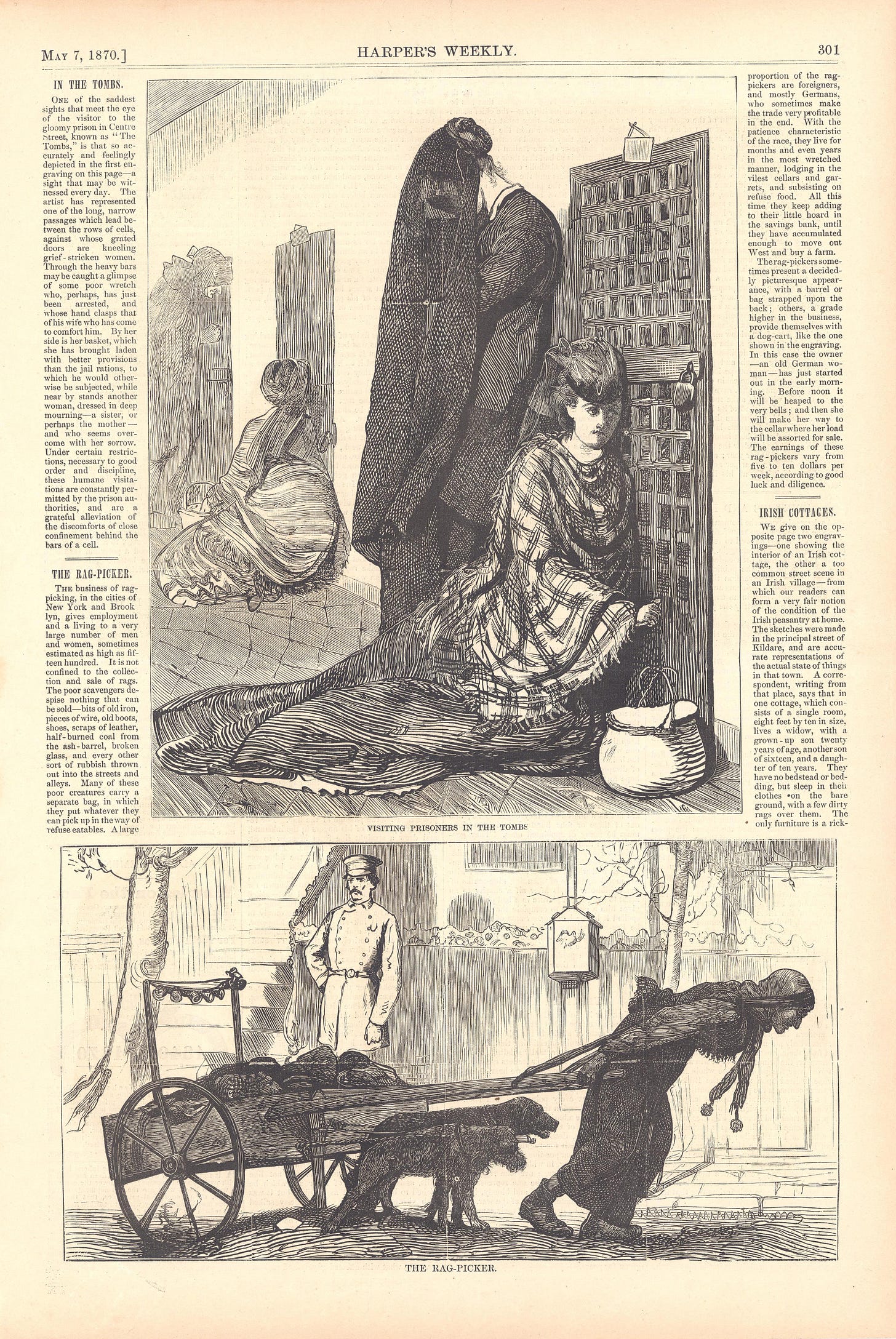

I have a wood block engraved illustration from Harper’s Weekly May 7, 1870 edition in my collection. Harper’s was the most popular illustrated newspaper/magazine of the 19th century in the United States. The antique print illustrates three women visiting the Tombs prison in NYC. It includes the following accompanying text:

“One of the saddest sights that meet the eye of the visitor to the gloomy prison in Centre Street, known as “The Tombs,” is that so accurately and feelingly depicted in the first engraving on this page–a sight that may be witnessed every day. The artist has represented one of the long, narrow passages which lead between the rows of cells, against whose grated doors are kneeling grief-stricken women. Through the heavy bars may be caught in a glimpse of some poor wretch who, perhaps, has just been arrested, and whose hand clasps that of his wife who has come to comfort him. By her side is her basket, which she has brought laden with better provisions than the jail rations, to which he would otherwise be subjected, while nearby stands another woman, dressed in deep mourning–a sister, or perhaps the mother–and who seems overcome with her sorrow. Under certain restrictions, necessary to good order and discipline, these humane visitations are constantly permitted by prison authorities, and are a grateful alleviation of the discomforts of close confinement behind the bars of a cell.”

Prison and jail visitation have been part of the experience of incarceration for generations. For a few years, Project NIA, my former organization, ran a prison visiting program that offered free rides to family members who wanted to visit their children incarcerated at Illinois youth prisons. Our program was in the lineage of others that were developed, especially in the 1970s like Connections based in San Francisco. Stay tuned in the new year for a resource by Reunification Rides to help others develop your own prison visiting projects.

This holiday season, incarceration and detention keep millions of people from their families. I wanted to offer some background about prison visitation to underscore its importance.

A Short History of Prison Visitation

“If you’re a parent, and your significant other goes to jail, it’s already extremely hard to raise your kids on your own, and to watch the toll it takes on your children,” Karla Darling told The New Yorker in May, 2024. Darling’s ex-husband, Adam Hill, was held in county jail in Flint, Michigan awaiting trial. His children, 18-year-old Le’Essa and 15-year-old Addy, could not visit him for an entire year.

Often, prison authorities prevent family members like Le’Essa and Addy from seeing their incarcerated parents. The hardship this causes is intense. One partner of a prisoner told the New York Times in 1971:

“There is no blanket formula for what to tell the children. Some say, ‘Daddy is in the hospital.’ Others that he is away at sea. Some tell the truth. Often the oldest child is the only one who knows. I tried to keep a cheerful facade when my husband was sent away, but one day I broke down completely and my 7‐year‐old was so relieved. She said, ‘I thought you didn’t miss Daddy. I thought you didn’t care about him any more.”

Prison authorities say this heartbreak is justified by security concerns. But restricting visitation in this way makes no one safer. On the contrary, allowing incarcerated people to see their families and loved ones benefits everyone.

First prison visitation reduces the likelihood that someone will return to prison after release. One Minnesota study, for example, found that prisoners who received visits were 13% less likely to reoffend once released. Researchers analyzing violence in a Knox County, Tennessee facility found that banning visits dramatically increased assaults and violence in the facility. Moreover, families of incarcerated people show better mental health outcomes, and children show improved behavior when they can visit incarcerated family members.

Despite the overwhelming evidence of the positive effects of visitation, however, there has been little effort to increase visitation opportunities in prison over time. Instead, in the past 50 years of hyper-incarceration, and in the past 30 years of the communication technology revolution, visitation policies in prisons and jails have, if anything, become more restrictive.

Parchman and Conjugal Visits

Researchers generally believe that “conjugal” visitation began in 1918 in the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman. In 1901, politicians built Parchman as a penal plantation where they forced Black men to harvest cotton. White overseers believed Black men had uncontrollable libidos and would become docile if allowed to have sex. So Parchman created an informal system of conjugal visits. They had the men build shacks out of red painted lumber, and bussed in spouses and sex workers who the men could visit in relative privacy.

Visitation rationales and rights slowly expanded beyond these ugly racist & anti-Black beginnings. In the 1930s, Mississippi allowed white men conjugal visits. A 1962 study of the expanded program reported that prison officials believed that sexual intimacy between spouses was a right, and that conjugal visits could help prisoners by assuring them of the well-being of their families. They also hoped visits would reduce same-sex relationships in prison and the incidence of prison rape.

In 1974, Mississippi began a Family Visitation Program, in which not just spouses, but parents, siblings, and children could visit together for 3 to 5 days in apartments provided by donations from local businesses and prisoners’ families themselves. Other states, such as California, South Carolina, New York, Minnesota, Washington, Connecticut, New Mexico, and Wyoming, instituted conjugal and family visitation programs from the 60s into the early 80s. Women prisoners began to be afforded conjugal rights in the 1970s.

Mass Incarceration and The Rollback of Visitation

Even at the best of times, visitation was difficult. Traveling to see relatives could be expensive and exhausting, especially with small children. Officials might deny access if a prisoner was not married to their partner. They restricted even letters, so prisoners could not always write to their children. Prison authorities could arbitrarily deny access, which made it difficult for families to advocate for themselves. “Their overriding fear,” one family member told, the NYT in 1971 “is that the prison might find out they were active and take reprisals against their husbands.”

The situation got even worse from the late 1980s, as the US moved towards a harsher approach to incarceration. Using flimsy scientific evidence, courts and politicians decided that rehabilitation programs were ineffective and that people in prison were incorrigible and deserved harsh and permanent punishment. President Bill Clinton signed multiple bills extending sentences and eliminating rehabilitation services and programs in prisons.

In line with these changes, states rolled back and eliminated conjugal visitation programs. South Carolina, Wyoming, and even Mississippi abolished conjugal visits; California put severe restrictions on the number of prisoners who could take part.

When prisoners attempted to sue for the right to see their families, they almost invariably lost in court. In 2003, in Overton v Bazetta, the Supreme Court ruled prisons could impose virtually any restrictions on visitations—even on visits by children and on non-contact visits.

Telecom industry changes exacerbated these issues. The government broke AT&T’s phone monopoly up in 1982. That led to lower phone prices for most people in the US. In prison, however, telecom companies signed exclusive deals with local officials. Exorbitant phone service rates were charged to prisoners and their families. A call to an incarcerated person in some prisons could cost as much as $20 for 15 minutes. Low-income families, sometimes, could literally not afford to talk to their loved ones.

Telecom’s War on Prisoners

The growth of the internet could have made prison communication cheaper and easier for families. That’s not what happened, however. Instead, in the early 2000s, the situation worsened further as large private equity firms merged into two massive firms, controlling communication in almost all prison facilities—GTL and Securus. These large firms moved to gouge prisoners and their families at every opportunity. They required prisoners and families to buy digital stamps to send email messages or photos and even charged prisoners by the minute to read books on tablets.

In the 2010s and 20s, communications companies also began to offer prisons new surveillance options for phone calls and communications. Some software is supposed to detect when people are discussing illegal activities. These products are untested and can flag people for innocuous conversations. The threat of surveillance also makes families and children afraid to speak openly to loved ones, turning connection with family into an exercise in paranoia and fear. “When I share really personal things about my own mental health to my dad, I don’t want random people listening,” Le’Essa Hill told the New Yorker.

The Covid pandemic was a disaster for prison visitation rights. During the pandemic, most facilities shut down in-person visits all together. Prisons mostly opened to in person visitation again after 2022 as vaccines and treatment became more available. But jails in places like Michigan and North Carolina have simply eliminated in-person visits all together, switching to for-pay video. Denying in-person visits punishes people held pretrial, even before a finding of guilt. Former prisoner Chandra Bozelko, writing for the Guardian in 2016, argued that video calls are no substitute for in-person visits. It was visits with her mother, she said, that “helped me to relearn the social graces that were lost while inside.”

The Fight for Visitation

Prisoners, their families, and advocates have had some successes in pushing back against the decades long reduction of visitation opportunities. In 2018, Massachusetts passed a law requiring facilities offering video visits to guarantee an in-person option as well. The federal government under President Biden made phone calls to federal prisons free during the height of the pandemic. Biden also signed legislation to allow the FCC to regulate state prison phone calls and set nationwide caps; it is supposed to go into effect in late 2024. In Michigan, families and civil rights groups are working on suing to insist that families have a legal right to visitation under the state Constitution.

One of the most successful efforts to allow families to see accused loved ones, though, is Illinois’ Pretrial Detention Act, which has eliminated the state’s use of cash bail. That means people cannot be held in jail simply because they do not have the funds to pay a bond. This has substantially reduced the number of people in jail; in Cook County, jail populations have fallen by 13%.

Thanks to banning cash bail, many people in Illinois who would have been in jail for weeks or months awaiting trial, separated from their spouses and children, are now at home with their loved ones. Other states mirroring this legislation will powerfully ensure that arrested people remain connected to their families and communities. One of the most effective ways to ensure that people can see their loved ones is to not incarcerate them in the first place.

Sources Consulted [not in order]

Chandra Bozelko, “Prison visits helped prepare me for life after release. Why are they under threat?” Guardian, April 20, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/apr/20/prison-vists-prepare-life-after-release-threat

Chesa Boudin, Trevor Stutz, and Aaron Litman, “Prison Visitation Policies: A Fifty-State Survey,” Yale Law & Policy Review, 32:1, 2013. https://law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/area/center/liman/document/prison_visitation_policies.pdf

Madeline Buckley, “6 months after Illinois Ended Cash Bail, Jail Populations Are Down As Courts Settle Into New Patterns,” Chicago Tribune, April 29, 2024 https://www.chicagotribune.com/2024/04/29/6-months-after-illinois-ended-cash-bail-jail-populations-are-down-as-courts-settle-into-new-patterns/

Sharon Cohen, “23 Hours a Day in Closet-Sized Cell: Marion: America’s Toughest Penitentiary,” Los Angeles Times, August 2, 1987. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-08-02-mn-747-story.html

Joan Cook, “Visiting a Prisoner: It’s Punishment for Family, Too,” New York Times, February 3, 1971. https://www.nytimes.com/1971/02/03/archives/visiting-a-prisoner-its-punishment-for-family-too.html?smid=em-share

Molly Hagan, “Controversy and Conjugal Visits,” JStor Daily, February 13, 2023. https://daily.jstor.org/controversy-and-conjugal-visits/

Sylvia A. Harvey, “2.7 Million Kids Have Parents in Prison. They’re Losing Their Right to Visit.” The Nation, December 2, 2015. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/2-7m-kids-have-parents-in-prison-theyre-losing-their-right-to-visit/

Martin Kaste, “Jails are embracing video-only visits, but some experts say screens aren't enough,” NPR, December 20, 2023. https://www.npr.org/2023/12/20/1219692753/jails-are-embracing-video-only-visits-but-some-experts-say-screens-arent-enough

German Lopez, “Family visits make prisoners less likely to reoffend. But some states make visiting hard,” Vox, October 22, 2015. https://www.vox.com/2015/10/22/9589052/prison-visits-recidivism

Minnesota Department of Corrections, “Effects of Prison Visitation on Offender Recidivism,” November 2011. https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/effects-prison-visitation-offender-recidivism

Bernardette Rabuy and Daniel Kopf, Separation by Bars and Miles: Visitation in State Prisons,” Prison Policy Initiative, October 20, 2015. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/prisonvisits.html

Tamar Sarai, “Prisons control incarcerated people’s relationships and their access to intimacy,” Prism Reports, February 13, 2023. https://prismreports.org/2023/02/13/prisons-intimacy-relationships-incarcerated-people/

Sarah Stillman, “Co Children Have a ‘Right to Hug’ Their Parents?” New Yorker, May 13, 2024. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/05/20/the-jails-that-forbid-children-from-visiting-their-parents

Christie Thompson, “Fighting the High Cost of Prison Phone Calls,” The Marshall Project, February 24, 2023. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2023/02/25/prison-phone-calls-colorado-biden-securus

Leah Wang, “Research roundup: The positive impacts of family contact for incarcerated people and their families,” Prison Policy Initiative, December 21, 2021. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2021/12/21/family_contact/

Prison visitation is in need of reform. It's seemingly getting harder for families.