Bill Epton and the Radical Struggle Against Police

Mid-20th Century US Anti-Authoritarian Organizing

Our Black Zine Fair is a couple of weeks away on May 3. RSVP here to attend. In the lead up to the fair, we’ve been hosting some virtual sessions and the final one is this Saturday April 26. RSVP here for that. I’m excited to share several brand new zines at the Fair. I’ll also have some buttons [thanks to my friend Sarah for designing them]. Stop by if you’re in NYC.

This is the final week for people to apply to teach a workshop or course at our 2025 NYC anti-criminalization Communiversity. Applications are due April 25 at midnight ET. Please share the opportunity far and wide.

I am raffling an embroidery I made to raise money for a family in Gaza. Anyone who donates at least $15 can enter the raffle which is open until April 24 at midnight ET.

Finally our children’s book “Prisons Must Fall” is out and it’s so beautiful. Pick up a copy where books are sold. You can find additional resources here.

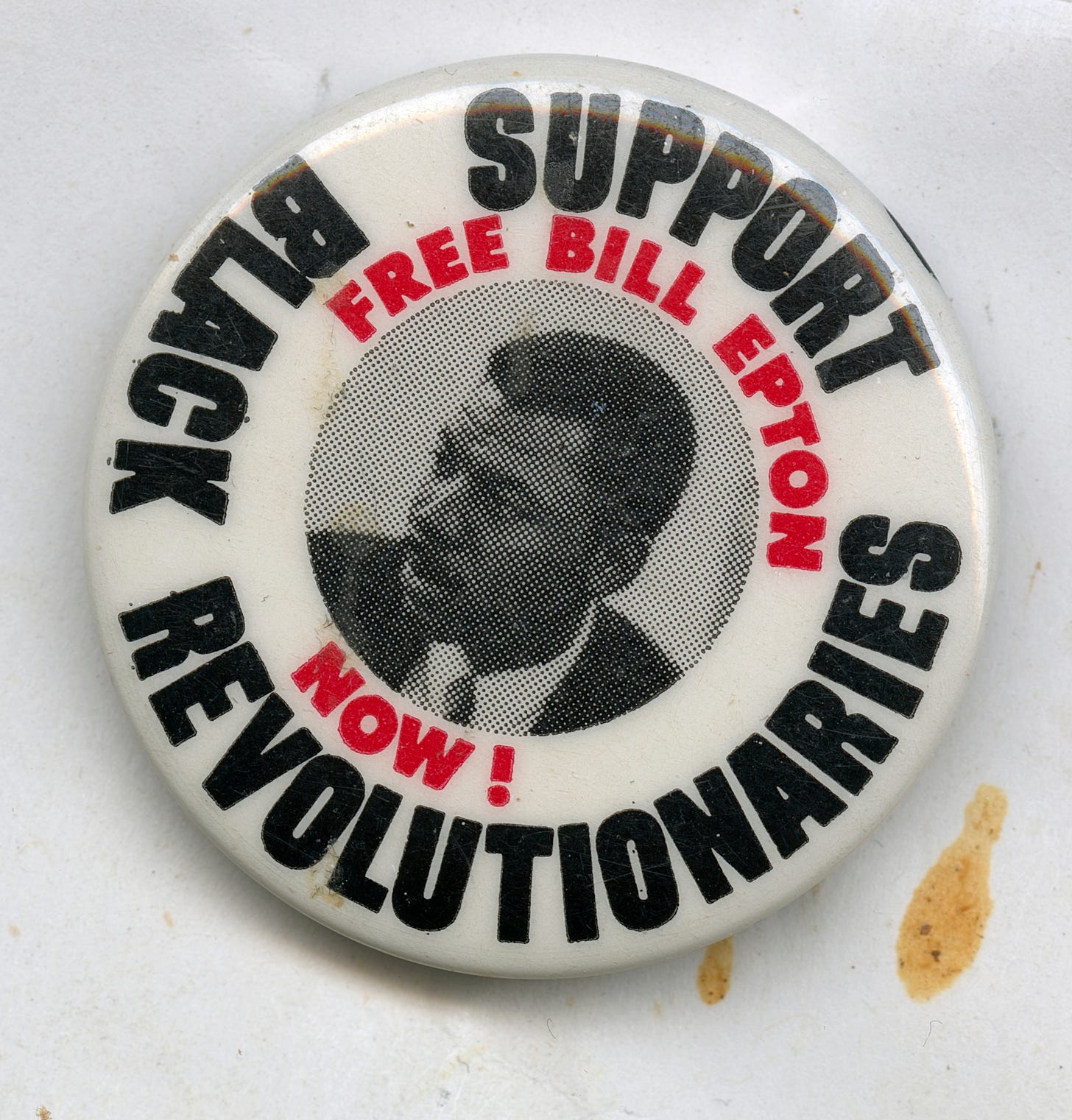

Years ago, I wrote about Bill Epton on my blog Prison Culture. I learned about him while I was writing a zine about historical resistance to police violence in Harlem. I ended up requesting his FBI file and my admiration for him deepened. Over the past few years, I’ve been collecting artifacts and ephemera related to his activism. I’m hoping that someone [not me] will write a full biography about him someday soon. He deserves at least one.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Epton lately because he boldly and consistently stated that the United States was already a police state in the 1960s. He would not be surprised by full on fascism in the U.S.

In the popular imagination, the Civil Rights Movement of the mid-60s is generally remembered as a pacifist, mainstream coalition focused primarily on voting rights in the South. This narrative, though, erases the radicalism of the time and the sometimes violent Black resistance in cities throughout the country to police brutality, the carceral state, and the American War in Vietnam. It also downplays the violent persecution Black activists faced in the North.

Bill Epton’s story highlights the forgotten and ignored aspects of civil rights struggles during the 60s. A courageous and radical critic of police brutality, Epton was targeted by the New York Police Department for surveillance and harassment. He eventually became the first person to be convicted of “criminal anarchy” in New York state since World War I.

In a fiery speech before the court after his conviction, Epton denounced the legitimacy of the criminal legal system and insisted on the right to, and necessity of, resistance. “I have been found ‘guilty’ of organizing the Harlem community against police brutality that has been occurring in the Black ghettos for hundreds of years,” he thundered. “I have been found ‘guilty’ of standing up for the right of all men to be free—to be free from the system of exploitation of man by man.”

Epton and the Progressive Labor Movement

William (Bill) Epton was born on January 17, 1932 to William Epton Sr., a laborer originally from Georgia, and Lucy Green Epton of New York. The young Epton attended DeWitt Clinton High School, where he became involved in the growing civil rights movement and in union organizing. The military drafted him in 1952, and he fought in the Korean War, earning two bronze stars. He received an honorable discharge in 1954.

On his return to Harlem, Epton worked as an electrician and machinist. He also became involved in radical politics. He joined the Communist Party in 1959, leaving in 1962. This did not indicate a break with radicalism, however, as he showed by organizing a Harlem chapter of the Progressive Labor Movement (PL), a Maoist organization.

According to one member, in most of the country, PL largely comprised young white students from middle-class families. But in Harlem under Epton, the chapter became a center of Black radical organizing. The PL created the Harlem Defense Council, which raised money for and publicized the case of the Harlem 6, a group of Black youth arrested, beaten, and charged with murdering a white store owner in April 1964.

The Harlem Riots of 1964 and Police Espionage

The Harlem 6 gained limited media attention. Another case of police brutality a few months later, though, ignited Harlem. On June 16 1964, Thomas Gilligan, a white off-duty police officer, shot fifteen-year-old James Powell, a Black student, outside of a Harlem junior high school. Conflicting reports emerged, but several witnesses stated Gilligan shot Powell without warning, firing twice more after Powell fell.

Powell’s death led to demonstrations, violent police reprisals, and a major riot that lasted from June 18 to 20th, spreading from Harlem into Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brownsville, and South Jamaica. The events resulted in one death, 100 injuries, and 450 arrests.

The riot was a response to police brutality. But the NYPD was desperate to deflect blame onto Black radicals and supposed subversives. PL became a major target in this strategy.

The NYPD’s Bureau of Special Services (BOSS) had infiltrated PL almost from its formation using a Black NYPD agent named Adolph “Abe” Hart. Hart was eager to show his worth so he could advance within the racist NYPD. He was well-positioned to report on PL’s activities related to Powell’s murder.

Those activities were extensive. Epton and PL prepared and released pamphlets on the day of Powell’s murder linking the youth’s death to other Black victims of police brutality and to an ongoing “police war on Harlem.” PL quickly located a picture of Gilligan and created a flyer that read “Wanted for Murder: Gilligan the Cop.” Protestors widely distributed the fliers, and many carried them. One flier even appeared in an image of the protest in Life magazine.

Epton made an impassioned speech on January 18, denouncing the racism of the police and the government. He called for “smashing the state,” and added, “in the process of smashing this state, we’re going to have to kill a lot of these cops, (and) a lot of these judges.”

The speech concluded at 6:00 PM without violence; the riot only started hours later. However, Hart had been present, transmitting the speech to another police officer who had transcribed it. On July 25, authorities officially arrested Epton for marching despite a post-riot injunction against demonstrations. But the speech on January 18 became a major factor in his indictment and prosecution.

Epton on Trial

A grand jury, convened for ten months, aggressively investigated Epton and jailed many witnesses for contempt of court.

The grand jury also reviewed Hart’s evidence, much of which proved uncorroborated. For instance, Hart claimed that PL members had shown him how to make Molotov cocktails, but the person he named had an alibi for the evening when she was supposedly instructing him. The only person on tape advocating the use of Molotov cocktails in a PL meeting was Hart himself.

Despite Hart’s lying and entrapment, and despite the lack of evidence linking Epton or PL to the riots, the court convicted Epton of criminal anarchy and sentenced him to a year in prison on February 2, 1966. At the sentencing, Epton delivered an unrepentant 45-minute speech in which he indicted the court and the nation for its racism, imperialism, and oppressive authoritarianism.

I have been found “guilty” of being an outspoken critic of the U.S. government and its paramilitary police force.

I have been found “guilty” of publicly advocating socialism to cure the ills of the Black people of the country and the workers in general.

And finally – I have been found “guilty” of being a communist – and a Black one at that!

If these are the “crimes” that I have been found “guilty” of committing, then I am “guilty” a thousand times over. In fact, I will be “guilty” of these “crimes” as long as the conditions exist, and I will fight against these conditions as long as there is a breath in my body!

The gallery, filled with Epton’s supporters, erupted in applause until the Judge angrily cleared the courtroom. PL quickly printed the speech as a pamphlet titled “We Accuse: Bill Epton Speaks to the Court.”

Epton’s Later Life

After serving his prison term in Rikers, Epton split with PL. He continued to try to build Communist resistance to police brutality and imperialism in the 70s. He died in 2002 of stomach cancer at 70.

Epton’s New York Times obituary argued that the Supreme Court changed the standards for incitement shortly after his imprisonment. The Times suggested that Epton would have avoided conviction if tried only a couple of years later.

Whether that is the case, Epton’s trial and conviction clearly show the lengths to which police, courts, and the state will go to repress Black radical resistance and Black radical critique. Just as police, courts, and the state harassed and repressed Epton, they are now harassing and repressing a multi-racial group of Cop City protestors in Atlanta. Today, as in Epton’s time, opposing the police is a radical act, and one that requires commitment and courage. “You may put me in your jail,” Epton declared, “but you cannot stop the march of my people towards freedom and liberation, and in the final analysis, when the last and most important voice is heard—it will be the voice of the people who will make the ultimate judgment—not on me, but on the U.S. government and those who carry out its policies.”

Sources Consulted

“Bill Epton,” Wikipedia, accessed January 6, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_Epton

Herb Boyd, “Bill Epton, A Political Activist and Free Speech Activist,” New York Amsterdam News, February 23, 2017. https://amsterdamnews.com/news/2017/02/23/bill-epton-political-activist-and-free-speech-advo/

Christopher E. Bruce, “RICO and Domestic Terrorism Charges Against Cop City Activists Send a Chilling Message,” ACLU, September 21, 2023. https://www.aclu.org/news/free-speech/rico-and-domestic-terrorism-charges-against-cop-city-activists-send-a-chilling-message

Bill Epton, “We Accuse: Bill Epton Speaks to the Court,” Marxist-Leninist Translations, accessed July 6, 2025. https://www.mltranslations.org/epton/

“Harlem Race Riot of 1964,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed January 6, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/event/Harlem-race-riot-of-1964

Mariame Kaba, “A Dispatch from ‘Occupied Territory’: James Baldwin & the ‘Harlem Six,’” Prison Culture, April 15, 2012. https://www.usprisonculture.com/2012/04/15/a-dispatch-from-occupied-territoryjames-baldwin-the-harlem-six/

Mariame Kaba, “Bill Epton: Resisting Racist Policing in Harlem,” Prison Culture, March 26, 2012. https://www.usprisonculture.com/2012/03/26/bill-epton-resisting-racist-policing-in-harlem/

Joseph Kaplan, “‘We Accuse’: The Harlem Rebellion, Bill Epton’s Anti-Carceral Activism, and the rise of the Surveillance State,” Gotham Center for New York City History, August 24, 2021. https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/we-accuse-the-harlem-rebellion-bill-eptons-anti-carceral-activism-and-the-rise-of-the-surveillance-statenbsp

Douglas Martin, “William Epton, 70, Is Dead; Tested Free Speech Limits,” New York Times, February 3, 2002. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/02/03/nyregion/william-epton-70-is-dead-tested-free-speech-limits.html

I would absolutely read a biography. Thank you for sharing Bill’s story Mariame.

I read Mariame Kaba but had not heard of Epton and his work. It seems he was easily labeled just because it made it easier to equate a response to police brutality as Anti-police rather then anti-brutality.