This is a love letter to my currently exhausted and perhaps even demoralized organizer and activist comrades and friends across the country…

In July, I had lunch with a friend from Chicago who had been feeling really down and questioning the value of their organizing work.

Organizing can be difficult and disheartening. There are always good reasons to feel discouraged. But I reminded my friend that the population detained at Cook County Jail is down 58% since 2013. In September of that year, the population hit a high of 11,248. In January 2024, that number had plummeted to 4,675.

My friend has been heavily engaged in abolitionist organizing since around 2010. Their work has focused on Cook County Jail. And yet, they could not take in this incredible fact that tens of thousands of people over the last decade have not entered Cook County Jail in part because of their efforts. Absolutely incredible.

Closing Youth Prisons in Illinois

The fall in the Cook County Jail population is a major win for organizers and our communities. It’s far from the only victory in the state, though. Youth incarceration rates in Illinois have also fallen precipitously. That directly results from organizing campaigns including ones I was involved with during my years in Chicago.

In 2013, eleven years ago, I spoke to writer Vikki Law at Truthout about our youth decarceration campaign. In the piece, I discuss our efforts to close youth prisons in Illinois. At that time, Governor Pat Quinn and the legislature were facing budget difficulties, and were interested in reducing prisoner numbers, hoping to save funds.

In 2011, the legislature, partially in response to activist organizing, passed a law encouraging alternatives to youth incarceration. That led to a fall in the number of youth in prisons and jails, creating momentum for further change.

My organization, Project NIA [along with others], took advantage of this opening. We pressured the governor’s office, creating fact sheets, holding teach-ins, organizing protests, to spread the word about the decrease in juvenile incarceration and the feasibility of closing facilities.

At first, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), the union representing prison employees, triumphed in its efforts to prevent closures. As I told Vikki, “They posted some horrific things about the youth on our Facebook, but it made people aware of the issue and question why such people were entrusted to guard youth. They ended up bringing people to our side.” I have other stories about my interactions with AFSCME members over the years that I will keep for another day.

By 2014, we had generated enough support that the governor could close two youth prisons, Murphysboro and Joliet. Quinn actually boasted about reducing prison numbers. “When I took office [in 2009], Illinois had 1,330 young people in juvenile detention centers. Today [in 2014] we have 857.”

Quinn took credit for the decrease. But organizers had been working on these issues long before he took office, and continued to push for decarceration after he left. And the results have been stunning.

The success of youth decarceration

In August, the Sentencing Project released a new report titled Youth Justice By the Numbers. It finds a 75 percent decline in youth held in juvenile prisons and jails in the US over the last twenty years—108,800 to 27,600 between 2000 and 2022.

Overall, The Sentencing Project’s report finds the arrest rate for minors has declined 80 percent through 2020 from its peak in 1996. Between 1997 and 2022, there was an 84 percent drop in youth held in adult prisons and jails.

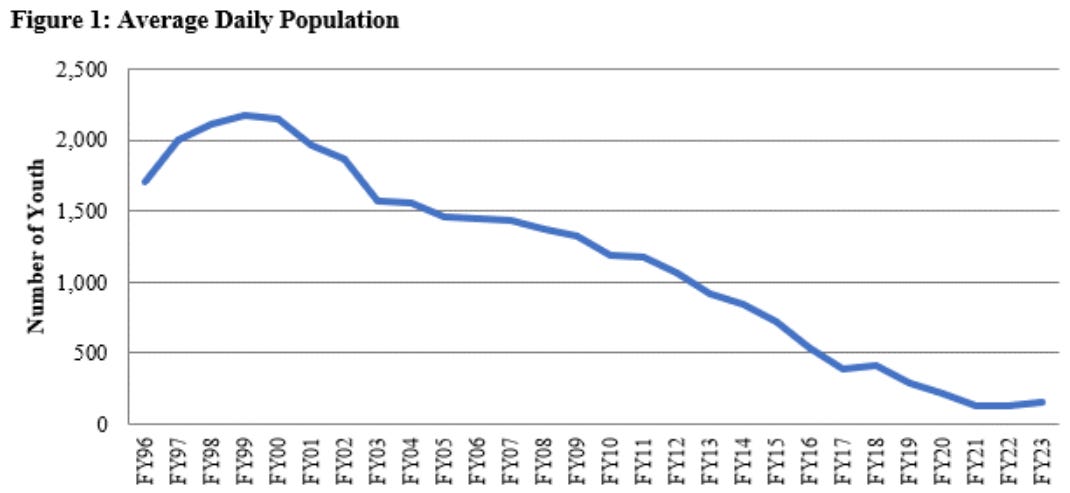

In Illinois, the placement rate for youth was 39 per 100,000 in 2023—the tenth lowest in the nation. The average daily juvenile incarcerated population has fallen dramatically in the state from a high of over 2000 in 1999 to only 154 in 2023 (it rose slightly to 170 in 2024).

IDJJ Population Chart, showing trend from 1996-2023 (p.15).

The decline here was not entirely because of abolitionist and other organizing. Youth arrests have fallen 84% since the late-1990s. This has created an opening for decarceration. Budgeting incentives have also helped. But abolitionist and other organizing campaigns have been key to turning these opportunities into concrete reductions in the number of young people in detention.

Defeating the critics

Abolitionist organizing is vital for change in part because politicians, legislators, police, prison guard unions, and other carceral advocates often see incarceration as a positive good no matter the situation, and resist all calls to reduce prison populations. Some reformers may also resist change for fear that any alteration to the current system will make things worse.

In Illinois, for example, advocates pushed to reduce the number of youth in adult court and adult custody. So far, the state has responded by raising the age to include 17-year-olds in juvenile court and reducing automatic transfer, first for drug offenses and then for a wider range of offenses. When the first change passed in 2002, critics said it would overwhelm and expand the juvenile system, requiring new youth detention centers and youth prisons to be built. Instead, as we’ve seen, the number of young people sent to adult court decreased and the overall rates of juvenile detention continued to fall.

The (successful!) effort to end money bond in Illinois has had to confront similar fears. Critics expressed concern that ending cash bail would cause judges to incarcerate people without bail and with no hope of release. Again, these fears have proven to be overblown. As one success story, the overcrowded St. Clair County Jail reduced jail populations by 19%, from 550 to 384, during the first 8 months after the state abolished cash bail.

That changes did not backfire in either of these cases wasn’t an accident. It resulted from a lot of very hard work by organizers and policy makers to make sure that reforms led to fewer, rather than more, people in prison.

Whenever advocates have made changes to reduce juvenile detention, both status quo defenders and allies with limited expectations have informed them that “the system is already diverting every possible youth from incarceration.”

They were told there were no other options for the youth remaining in prison and no hope of significant change.

Year after year, the falling youth incarceration rates proved this false. And yet, year after year, abolitionists and reformers were told again that the next step was impossible and would lead to disaster. In other words, people despaired of change while in the process of making it!

Much more needs to be done

Abolitionist organizers in Illinois have had many successes. But the criminal punishment system remains a carceral system, and that means it remains discriminatory and violent.

For example, the Sentencing Project reports that in 2021, Black youth were 4.7 times as likely to be incarcerated as white youths. Native youth rates were 3.7 times those of white peers, and Latino youth were 16 percent greater than white youth. This is in part because white youth are more likely to receive probation and informal sanctions.

There are other limits to progress as well. Illinois is not only continuing to operate five youth prisons for the 170 youth daily incarcerated, but is currently building a sixth in Lincoln, IL. It is also looking to turn Harrisburg, and perhaps other facilities, into “emerging adults” prisons. These are to be run by IDJJ for a small fraction of youth (maybe 60) who would otherwise be in the Illinois Department of Corrections. This is a “reform” which has the potential to be truly terrible for young people, as adult court judges feel empowered to sentence more 18-21-year-olds to prison for “services.”

As long as there are prisons, abolitionists will need to organize against them. The persistence of incarceration, policing, violence, and advocates of all of those things can make it seem like the work is hopeless, or that abolitionists have accomplished nothing. When conditions actually worsen—when, for instance, prisons actually make it more difficult for incarcerated people to communicate with their loved ones—it's easy to give in to despair. But despair, as Audre Lorde has taught us, “is a tool of our enemies.”

If you’ve been part of freeing a single person from the torture chamber, that is our criminal punishment system, that’s truly amazing. And if you are among those involved in keeping hundreds and thousands of children and youth out of the state prison system over two decades, you have made an amazing difference repeatedly. Keep going!

Sit with these wins, take them in, and continue to struggle until everyone is free. And importantly, surround yourself with a community that will remind you that this is a miracle on earth.

While you are in struggle, sometimes all you can see is the ongoing struggle. But it’s important to take time to notice the things you’ve been part of changing. We have to celebrate our wins, no matter how small. This is the fuel to keep us going and this is inspiration that we need.

Note: My gratitude to Stephanie Kollmann who helped surface some reports and was a helpful thought partner.

If you appreciate this newsletter, please share it with others and importantly please click the heart icon so that more people can find it.

Sources Consulted

Children and Family Justice Center. “Restoring the State Legacy of Rehabilitation and Reform,”vol. 1, January 2018.

Dholakia, Nzish. “Prisons and Jails Keep Making It Harder for Incarcerated People to Communicate With Loved Ones,” Vera, December 13, 2022.

Equal Justice Initiative. “Illinois Becomes the First State to Abolish Cash Bail,” September 20, 2023.

Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice. Annual Report 2023. Accessed October 22, 2024.

Law, Victoria. “Closing Cages: People Power Helps Stop Youth Incarceration,” Truthout, March 11, 2013.

Maxwell, Mark. “Nearly 8 months into Illinois' new era without cash bail, experts say recidivism and jail populations are trending lower,” ksdk.com, May 7, 2024.

Mitchell, Chip. “Cook County Jail population has shrunk dramatically, but costs have not. Why?” Chicago Sun-Times, February 7, 2024.

Rovner, Joshua. “Youth Justice By the Numbers,” The Sentencing Project, August 14, 2024.

Schiraldi, Vincent. Interview with Michael Martin. “Youth crime is down, but media often casts a different narrative,” NPR: All Things Considered, September 4, 2022.

Shriver Center on Poverty Law, “Ending cash bail keep families together, communities safe and strong,” June 3, 2024.

Szanyi, Jason. “Reforming Automatic Transfer Laws: A Success Story,” Center for Children’s Law and Policy, December 2012.

Definitely needed. Thank you so much. I contributed to the Final 5 campaign which I didn’t know about before this post.

Thank you for the uplift—sorely needed! And always a useful reminder