It’s been two years since I launched this newsletter. I do not know where the time has gone. I’ve appreciated having a place to share thoughts, ideas and resources related to my interests. Thanks to everyone who reads and shares the newsletter. To celebrate this anniversary, this is a special Women’s History month feature about someone who I want more people to know: Louise E. Jefferson.

Also I’ll be sharing a new zine that I was invited to make at an event at the Free Black Women’s Library in Brooklyn on March 29. Details are here. In addition, don’t forget that the Black Zine Fair is coming up on May 3. Come celebrate Black DIY publishing in NYC.

Finally, the 2nd organizer co-working/drop in space that I am hosting is on March 30. Organizers who need some dedicated time to get work done are welcome. Bring your work and your good humor.

A few years ago, I learned about Louise E. Jefferson, one of the very few mid-20th century Black women cartographers in the U.S. Louise E. Jefferson (1908-2002) was an African-American artist, cartographer and publishing executive who worked in a wide range of genres and mediums, from photography to book cover design and children’s book illustration.

One of Jefferson’s most striking achievements is a series of five maps she created between 1944 and 1965 to illustrate the achievements and history of Black and marginalized people in the US and Africa.

These visually engaging maps challenge traditional ideas of cartography. First, a Black woman artist, rather than white male cartographic professionals, created them. Second, they are conscious aesthetic works of advocacy and resistance, rather than supposedly objective delineations of the default status quo. In a 2021 article in Cartographica, scholars Reagan Yessler and Derek H. Alderman argue that Jefferson’s work is an example of “counter-mapping” because her work “carves out a space for African American narratives and visions in the larger, white-dominated space.”

Biography

Louise “Lou” Jefferson was born in 1908 in Washington D.C. Her father Paul was an engraver/calligrapher for the US Treasury; her mother, Louise, was a musician who sang on Potomac River cruise ships. As a child, Lou contracted polio. Despite leaving her legs crippled, she became a local swimming champion and certified lifeguard. Louise gravitated to art and photography from an early age. She studied calligraphy, art design and lithography at New York City’s Hunter College, which at the time had one of the largest groups of Black women students in the country. While taking classes at Hunter, she shared an apartment above a Harlem funeral parlor with civil rights activist and fellow Hunter College student Pauli Murray. She then moved on to study graphic arts at Columbia University, though in the depths of the depression she ended up unable to graduate from either.

After college, Jefferson stayed in Harlem Renaissance New York City. To make ends meet, Jefferson continued doing freelance design work for the YWCA and the National Urban League. In 1935, when she was 27, she became one of the founding members of the Harlem Artist’s Guild, whose members included Augusta Savage, Gwendolyn Brooks and Jacob Lawrence. Around this time, she also began designing the NAACP’s annual holiday seal, a yearly project she would continue for 40 years. The NAACP designs used paper cutouts to form flat areas of color and often allowed Jefferson to display her expert calligraphy.

Jefferson’s best-known illustration project was a 1936 children’s song book whose title, We Sing America, nods to Langston Hughes’ poem, “I, Too, Sing America.” Her energetic line art shows children of multiple races and ethnic backgrounds playing, singing and going to school together. Georgia’s segregationist Governor Eugene Talmadge banned the book and publicly burned copies.

A self-taught photographer, Jefferson took pictures of figures like Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, and Eleanor Roosevelt, and was good friends with Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes, who she called “a doll.”

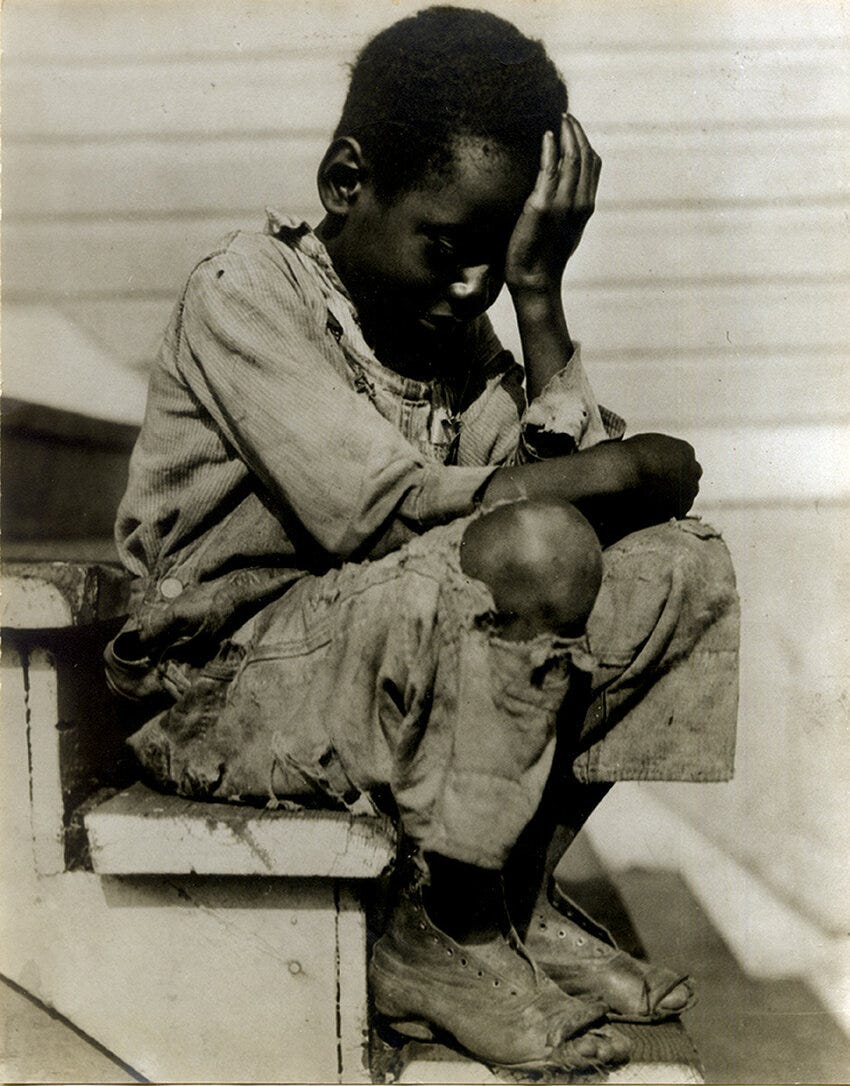

Her most famous photograph dates from around 1940, when Jefferson was visiting Tuskegee University. “I wandered off the campus, trying to get the feel of Alabama, which I didn’t much like,” she recalled in later years. She came upon an African-American boy weeping because no one would give him a penny. Like Walker Evans’ portraits, the image seems to sum up the hardship of poverty and the Great Depression. After taking the picture, Jefferson gave the boy a nickel—“and that’s when he really did cry.”

In 1942, Jefferson became the art director for the children and young adult branch of Friendship Press, the publishing branch for the National Council of Churches. She was the first African-American art director in US history, and may have been the first woman. Lou was an artistic polyglot. Reflecting on her experience, she said: “A commercial artist must have an encyclopedic mind–for you can never tell what you will be called on to depict or interpret.” It was at Friendship Press that she designed her maps.

Jefferson’s Counter-Maps

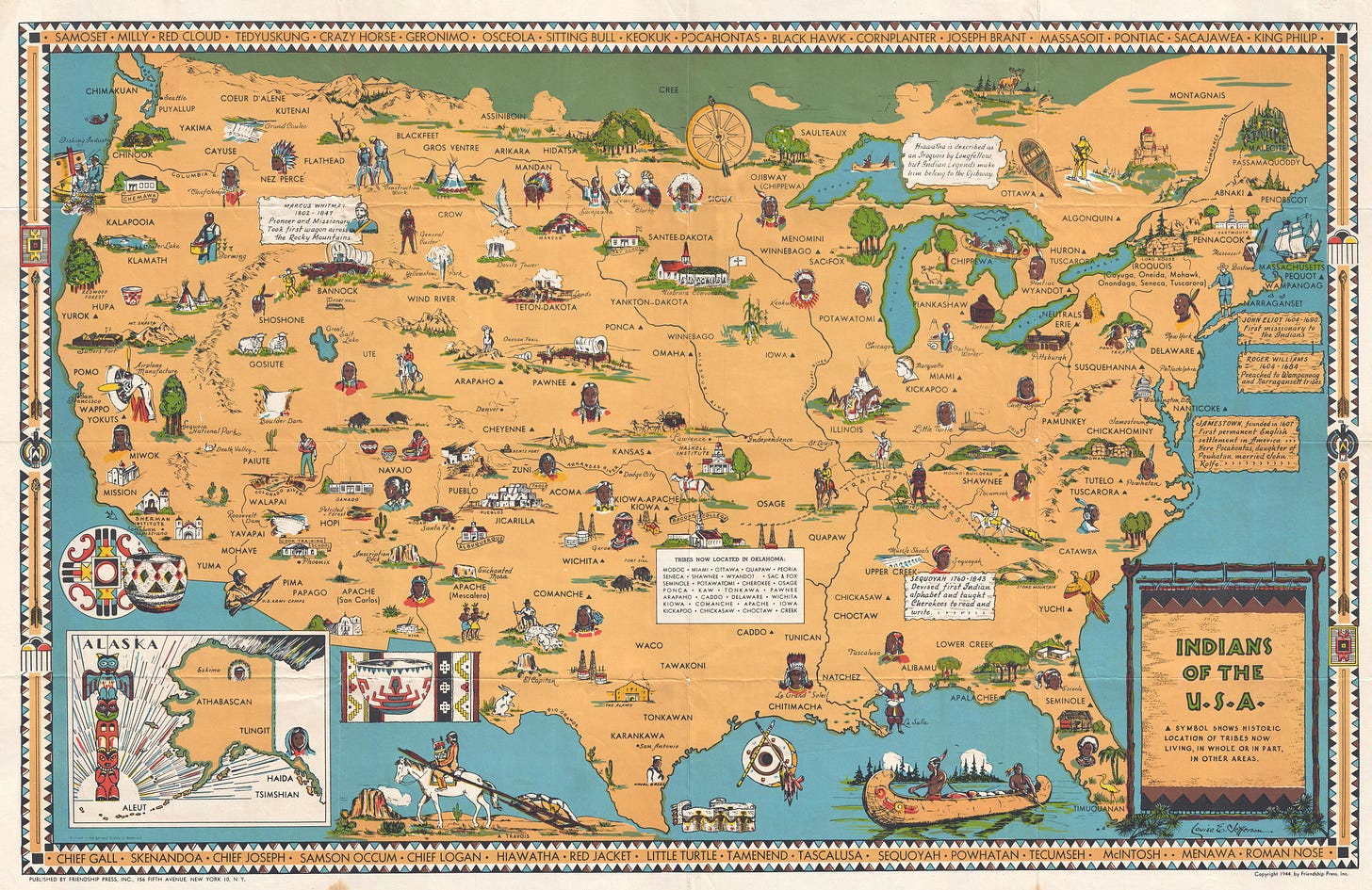

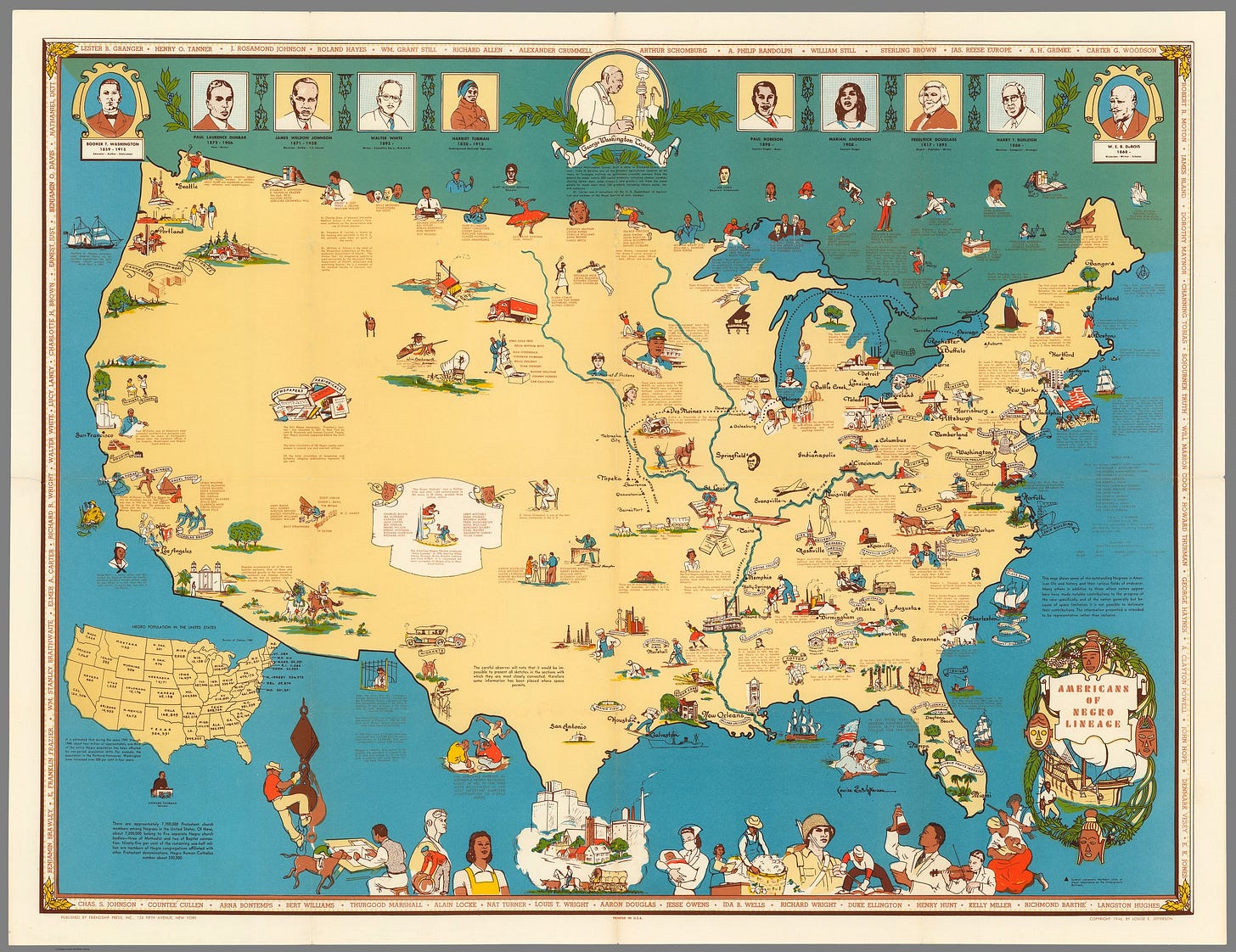

The four maps Jefferson designed in the 40s were Indians of the United States (1944), Uprooted People of the U.S.A. (1945), Africa: A Friendship Map (1945) and Americans of Negro Lineage (1946). The maps were designed for classroom use, and each include colorful illustrations and text on a map outline. You can view the maps in this blog post by the Library of Congress.

Yessler and Alderman argue maps may be counter-maps when they are created by marginalized groups to exert self-determination, and when they challenge normative ideas of what maps should look like. Jefferson’s maps fit both criteria. Jefferson was almost certainly one of the few African-American woman mapmakers of her day. More, her maps challenge traditional notions of mapmaking by insisting on the presence of Black people and other marginalized people on the land and in history.

The first map, Indians of the United States, provides a blueprint for the rest. Jefferson includes images of important historical figures—Geronimo, Sequoyah, and Daniel Boone. But she also draws common people—native people are shown tending sheep in Comanche territory in Texas, doing construction work in the upper West near Blackfeet and Flathead land, and working in commercial fishing boats off the Pacific Northwest coast by Chinook territory.

Jefferson thus shows that native people are not just a part of history, but are a part of a living present; they are on the map now. She draws indigenous people to show their presence rather than (as is often the case in representations of Native Americans) to show their absence.

Similarly, Africa: A Friendship Map from 1945 includes historical events and personages, but also includes modern textile factories and airplanes, along with a note that refutes colonial arguments for Black people’s incapacity. “There is hardly a type of responsible position in Africa today that is not being capably filled somewhere on the continent by an African,” Jefferson writes in one text segment on the map. “Africans…are teachers, college professors, nurses, doctors, dentists, lawyers, clergymen, engineers and business men.”

On the 1946 Americans of Negro lineage map, Yessler and Alderman point out, Jefferson uses “clever shading and colour schemes rather than simple black and white ink work to show the different shades of skin.” Along the top of the map, Jefferson includes illustrated portraits of prominent African-Americans like poet Laurence Dunbar and scientist George Washington Carver, rendered with individual, distinct faces that serve as a sharp contrast to, and a rebuke of, the racist blackface iconography prevalent in white illustrations of the time. Similarly, on Jefferson’s last extant map from 1965, 20th Century Americans of Negro Lineage, Jefferson takes advantages of advances in printing techniques to include actual photographs of important figures like James Baldwin and Thurgood Marshall.

The drawings on both maps emphasize positive achievements. But Jefferson is careful to show those achievements are not just the accomplishment of a few talented exceptions. There are drawings of Black people farming, serving in the military as WACS, and accompanying early Spanish explorers. Again, Jefferson draws Black people into the landscape and into history, envisioning them as an inseparable, ongoing presence in American life.

Later Life

Jefferson retired from the Friendship Press in 1960, though she continued to do some work for them (like her final map) and other publishers. Between 1960 and 1972, she traveled to Africa four times. On her trips, she gathered material for her last grand project, a book called The Decorative Arts of Africa, by the Viking Press in 1973, when Jefferson was 65. The volume includes 300 of Jefferson’s photographs and drawings, including illustrations of African textile patterns and full-length drawings of African clothing. The book became the basis for an exhibition at Trinity College in Hartford, CT, in 1984.

Jefferson had by that time herself settled in Litchfield, CT, where she lived with her beloved enormous white cat and continued to draw, garden and photograph into her late 80s. She kept a camera on the bookshelf by her apartment door, because, she said, “You’ve always got to be ready to catch the rhythm. Rhythm is always changing, even in the places and the people you see, day after day.” We now know she caught that rhythm not just in photographs and drawings, but in maps too.

References

Tasheka Arceneaux-Sutton, “A Black Renaissance Woman: Louise E. Jefferson,” in Briar Levitt, ed., Baseline Shift: Untold Stories of Women in Graphic Design History, Hudson, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2021, pages 22-31.

T. J. Banks. Sketch People: Stories Along the Way. Bloomington, IN: Inspiring Voices, 2012. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Sketch_People/

“Black History Month: Honoring Louise E. Jefferson,” University of Colorado Boulder-University Libraries, February 20, 2023. https://www.colorado.edu/libraries/2023/02/20/black-history-month-honoring-louise-e-jefferson

Granger, Lester B. (March 4, 1947). "The Credit Line is Lou's". Opportunity Journal of Negro Life

“Drawing Inspiration from Pauli Murray,” Pauli Murray Center for History and Social Justice, April 14, 2020. https://www.paulimurraycenter.com/words-from-the-center/2021/2/10/drawing-inspiration-from-pauli-murray

Diana Stuart Jones, “Photographer Dies At 93,“ CT Insider, January 9, 2002. https://www.ctinsider.com/news/article/Photographer-Dies-At-93-16856372.php

Julie Stoner, “Louise E. Jefferson—A Hidden African American Cartographer,” Library of Congress Blogs, February 7, 2022. https://blogs.loc.gov/maps/2022/02/louise-e-jefferson-a-hidden-african-american-cartographer/

Reagan Yessler and Derek Hilton Alderman, “Art as ‘Talking Back’: Louise Jefferson’s Life and Legacy of Counter-Mapping,” Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 56:2, 2021, pp. 137–150. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/797596

love the maps!!!

I love how you described her as an artistic polyglot. Thank you for highlighting and sharing this history.