In this month’s edition of Prisons, Prose & Protest, I share some thoughts about bail and some Black history. I share new publications by Sojourners for Justice Press (SJP), I recommend two podcasts about jails and several good recent articles, and much more….

Over 150 of you participated in the raffle for the 2024 Transformative Justice calendar! I had promised to select three winners but based on the interest, I used a random raffle app to pick six winners. Congratulations to Sloane, Kiera, Tuhfa, Cat, Natalie, and Rebekah! This was fun so I’ll do more raffles in the future.

Finally, SJP would like to make our publications available at no cost to incarcerated people and some educators who would like to use them in their classes. We are fundraising. If you would like to help, please donate here.

Prisons/Policing

In the US, the number of people held in pretrial detention exceeds 400,000 daily, with 7 million people passing through our jails each year. Over 60% of these people are in jail simply because they cannot afford bail. They have not been convicted of any crime, but poverty prevents them from affording bail, so they sit in a cell waiting for their day in court.

Last month, I watched How We Get Free, a short film about cash bail. It follows Elizabeth Epps, an abolitionist lawyer and organizer in Denver, who is the executive director of the Colorado Freedom Fund and a Colorado state representative. The film, which MAX is streaming, was shortlisted for an Oscar. I’ve had the pleasure of following Elizabeth’s work through social media over the past few years. It's great that more people have the opportunity to learn about her work now.

When community bail funds post bail, they are not only facilitating the liberty of a defendant, they may also change the eventual outcome of that defendant’s criminal case. Those can be abolitionist aims if the outlook is expanded beyond individuals to transforming the overall racist, classist, heterosexist, ableist, transphobic criminal punishment system.

For many years, people overlooked the role of local jails in creating the institutional foundations of mass incarceration and criminalization. This has changed in the last decade. By focusing on jails, organizers have helped to shift the narrative about how the US became a prison nation. They’ve also correctly framed bail/bond reform as an antipoverty measure by underscoring the role that jails play in our epidemic of criminalization.

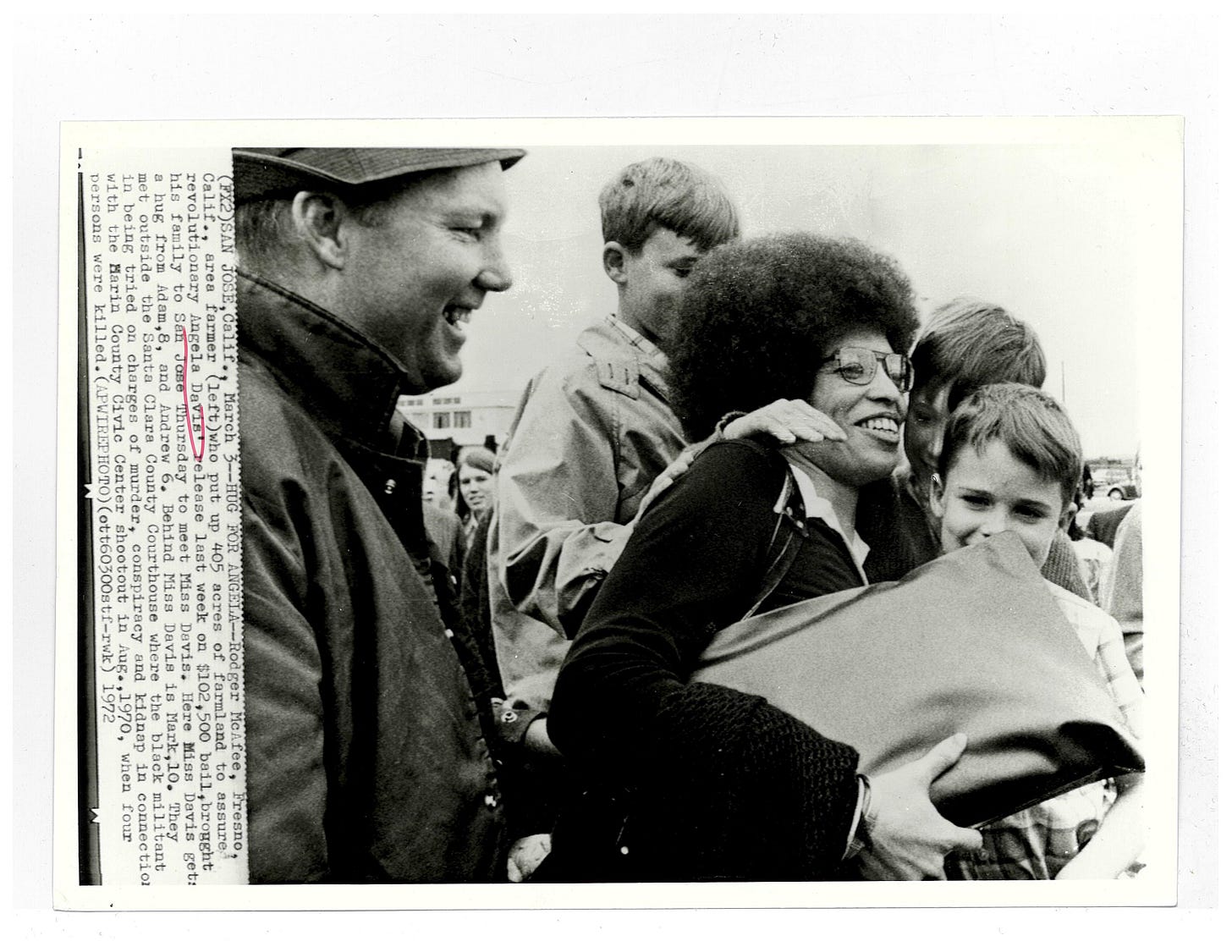

I have many vintage photos of Dr. Angela Davis in my collection. Below is one of them.

When Angela Davis was arrested in NYC in October 1970, a federal judge set her bail very high, at $250,000. But the outcry and mobilization that followed could have raised the amount needed to free her.

In a November 1970 statement, Aretha Franklin wrote:

“Angela Davis must go free. Black people will be free. I’ve been locked up (for disturbing the peace in Detroit) and I know you’ve got to disturb the peace when you can’t get no peace. Jail is hell to be in. I’m going to see her free if there is any justice in our courts, not because I believe in communism but because she’s a Black woman and she wants freedom for Black people. I have the money; I got it from Black people—they’ve made me financially able to have it, and I want to use it in ways that will help our people.”

When the federal prosecutors realized that bail would be posted, they took action and transferred Angela's case to the New York State authorities while revoking the federal bail. Angela Davis was to sit in prison. No bail—high, medium, or low—would get her out. She sat in the New York Women’s House of Detention for 2.5 months without bail. Then, authorities transferred her to Marin County Jail in late December 1970, where they held her without bail for months.

The National United Committee to Free Angela Davis (NUCFAD) launched a petition calling for her release on bail. They catalyzed resolutions for bail and launched a broad-based mass campaign for Angela’s release on bail.

When a Marin County judge denied Angela’s bail motion on June 15, 1971, Franklin Alexander, co-coordinator of the National United Committee to Free Angela Davis, said: “Judge Anrason’s decision proves what we have been saying all along: a Black person can’t get a fair trial in this court. We’re going to take this trial where justice will be given to our sister, and that’s in the streets. The power of the people will free Angela Davis.”

The fight for Angela’s release on bail was an integral part of the broader movement to win her complete freedom. The key argument in the fight for her release was that she was illegally being denied her right to pretrial release on a reasonable bail.

The demand for bail took various forms, with different tactics being used. There was a petition drive. People collected signatures at various locations, including door-to-door, supermarkets, union halls, churches, high schools, and colleges. The American Federation of Teachers, among other organizations, started its own successful petition drive.

The NUCFAD wrote in a pamphlet that documented their efforts at securing bail:

“The seemingly simple act of signing a bail petition was for many people a first step from which they moved to other kinds of defense activity: frequently, a petition signer asked for more petitions which he himself could circulate. Lively discussion about the case arose on street corners and other places where the petitions were passed out. Often a signer would express a pessimistic view that petitions alone were meaningless, and a discussion would follow of the purposes and functions of the petition drive, concluding with an invitation to become further involved in different kinds of ‘Free Angela’ activities.”

Coretta Scott King, Dr. Ralph Abernathy, and many others wrote statements to support releasing Angela on bail. The NUCFAD framed bail as a political weapon that was being used against Black and poor people to unjustly and illegally detain them. They wrote:

“In NYC, however, money bail is set in 85% of all felony cases—and well over half of these alleged felons are held because they can’t afford bail. But of these people, more than 1/3 are later acquitted of all charges, and another large percentage are convicted but given suspended sentences. Who are these people who spend months and years behind bars despite their right to bail and freedom? In NY, there are poor Blacks and Puerto Ricans, for the most part – and they number in the tens of thousands every year, jamming and overflowing the city’s ancient and dilapidated jails.

Most people have no idea of the larger number of brothers and sisters who languish behind bars because they can’t make bail. It’s generally thought that everyone has access to bail bondsmen whose activities are carefully regulated by law.”

Doesn’t this sound eerily familiar?

As already mentioned, Aretha Franklin had offered to pay Davis’ bail but was out of the country when Davis had her last bail hearing. The judge granted her bail at that hearing. Roger McAfee, a white farmer from Fresno County who sympathized with Davis, took out a second mortgage on his farm and gave her the money she needed for bail. Five days before her trial, on February 23, 1972, the judge approved bail for Davis for the amount of $102,000, and she could finally leave jail after serving seventeen months.

The NUCFAD was clear-eyed in linking its fight to free Davis with a broader fight to free all prisoners:

“A political attack on the bail system as a racist system of pre-trial detention has to be mounted in all prominent political cases. But the attack, to be successful, must not only result in the freeing of a particular captive. It must also bring massive, organized pressure to bear on the whole oppressive bail system itself. Political activists are captured and incarcerated because their struggles point towards the liberation of all oppressed peoples. Only when the burden of oppression has been lifted from the shoulders of all their brothers and sisters will political prisoners be truly free.”

The fight to free Angela Davis and the use of bail to hinder her release offer valuable lessons. I’ve spent many years working to bring awareness and organizing with others around bail. It’s been fascinating to me to see how much good organizing around the issue has happened, especially since 2015.

In January 2017, I attended a bail reform convening organized in Atlanta by the Movement for Black Lives Policy Table—a coalition of racial and economic justice groups of which I was a member. It was at that meeting that Mary Hooks, who at the time was codirector of Southerners on New Ground said: “Let’s bail our mamas out for Mother’s Day.” The idea lit up the room. With that, the National Black Mamas Bail Out mobilization, which aims to bring attention to this urgent social problem and the need to end the money bail system, was born.

Later that year, in December, I spearheaded #FreeThePeopleDay which led to the raising of hundreds of thousands of dollars and the release of hundreds from jail. In the ensuing years, #FreeThePeopleDay has raised millions and freed thousands. The fight to end cash bail and, most especially, pretrial detention continues. There is much more work to do. What part will you play? Bail funds are currently being criminalized in Georgia, with other states including Washington, Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and others considering similar measures. Please get educated about what’s happening and fight back.

For those who are interested in community bail funds, I recommend reading Jocelyn Simonson’s recent book, Radical Acts of Justice: How Ordinary People are Dismantling Mass Incarceration. In it, there’s a useful chapter focused on community bail funds. You can also visit the National Bail Fund Network website to learn about funds in your communities.

Reference:

National United Committee to Free Angela Davis. Bail for Angela: Right Without Remedy. San Francisco, 1971.

Publishing

Over the past couple of years, I’ve worked on a zine about a riot that took place at the United Nations. It’s a story I heard about from my dad and I was always interested in learning more. It features an incredible cast of characters. Sam Modder beautifully illustrated the zine—check out her other work here. After a delay, the zine, published by Sojourners for Justice Press, is now available for purchase here.

SJP has three new posters available in our Black Women, Violence and Resistance series. This time, artists Malachi Lily, Kyle Richardson, and Marika Bailey created posters inspired by Rose Butler, Frances Thompson, and Hattie McCray.

During the racist Memphis Massacre of 1866, Frances Thompson, a Black trans woman, suffered a vicious assault. Her congressional testimony inspired important civil rights gains during Reconstruction.

Frances was born in Alabama and grew up enslaved in Maryland. Following emancipation, she moved to Memphis, where she worked as a seamstress.

On May 1, 1866, several Black people in Memphis, including former Union veterans, held a block party. Police attempted to arrest the party-goers, the veterans resisted, and police and other whites rioted. Over three days, white mobs killed 46 people and burned down four Black churches, four Black schools, and 91 homes.

A group of seven white men, including police officers, attacked Frances and her sixteen-year-old housemate Lucy Smith in their home. They raped Frances and Lucy at gunpoint and robbed them of hundreds of dollars. Lucy said she was so badly injured, “I thought they had killed me.” Frances was sick for two weeks after the attack.

Months later, Frances delivered painful, riveting testimony about the massacre at a congressional hearing. She noted that the men who attacked her had boasted of their Confederate sympathies.

Her words, and the Memphis Massacre itself, turned public opinion strongly against neo-Confederate violence. Congress soon passed the 14th Amendment to the Constitution and other legislation that guaranteed the political and civil rights of Black people.

Ten years later, in 1876, police in Memphis arrested Frances for unknown reasons, and discovered that she was trans. Memphis authorities tried to use this to discredit her 1866 testimony, falsely insisting that she could not have been sexually assaulted.

The court sentenced Frances to labor in the city's male chain gang and forced her to wear men's clothing. She experienced further abuse while in prison. After her release, she was seriously ill and died of dysentery in 1877 or shortly thereafter.

Prose

This review by my friend Dan Berger of two recent books examines the expansiveness of carcerality in the US. As Dan writes, the prison shows up “wherever we find the state engaged in potentially lethal repression,” including in the historical reformatories, religious institutions, jails, and asylums featured in the books he discusses.

I love this meditation in Margaret Killjoy’s newsletter on how movements need to create room and invitations for all sorts of people to join and contribute their unique skills.

In this excerpt from the Foreword to a new book on jails, Ruth Wilson Gilmore explores with her usual power and insight the particular characteristics of carcerality in jail form.

I hope everyone will read this deeply personal essay by Palestinian American writer Sarah Aziza in which she explores the meaning, limits, and agony of bearing witness. As she writes, “Three months into a livestreamed genocide, we must ask—what does all this looking do?”

In this entry in Society Space’s collection of essays in response to Robyn Maynard and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s book Rehearsals for Living, Karyn Recollet offers a beautiful and illuminating tribute to the openings created by this unusual and special book.

Podcast

These two podcast episodes are good to listen to together: one focuses on the history of Cook County Jail and the other focuses on the current manifestations of jails.

In this episode of Unsung History, host Kelly Therese Pollock talks with Dr. Melanie Newport about what the history of Cook County Jail can teach us about racism, politics, and jailing as an institution.

This episode of This Is Hell offers a broader look at jails and jailing in the US as host Chuck Mertz discusses the issue with scholars Jack Norton and Judah Schept.

Poem

“The Birthday of the World” by Marge Piercy offers such a valuable reflection on where we put our “self-improvement” energy. And also such a beautiful articulation of the prayer that guides so many writer-organizers: “Let my words turn into sparks.”

Potpourri

Liberation Library is nine years old and it’s hard to believe! I cofounded this project and it has since been stewarded and expanded by a dedicated and brilliant group of volunteers in Chicago. Please consider donating to its continued work and attending their in-person fundraiser on February 24.

Sojourners for Justice Press is organizing a Black Zine Fair (BZF). BZF is a celebration of all things Black and publishing in New York City! We invite Black exhibitors and educators to gather, trade or sell zines, and exchange knowledge surrounding zine-making, self and independent publishing, and do-it-yourself culture. Learn more at the BZF website.

We’re reading about abolitionist Samuel Ringgold this month in our Life Stories of Anti-Slavery Abolitionists reading and discussion group. Join us! Register here.

Last year Project NIA offered some financial support to @realyouthinitiative for a political education project about Martin Sostre. They produced a new zine focused on the life and legacy of Sostre. The zine includes art, photographs, and handwritten text created by incarcerated young people. You can purchase the zine here.

Meneese Wall -- I first saw the beautiful cards created by Wall in the gift shop of the New York Historical Society. I have since purchased a number directly from Wall’s website. Here are some notecards and prints appropriate for Black History Month.

I enjoyed Stromae’s Tiny Desk Concert.

People who know me know how much I absolutely love tea. A friend sent me a Red Velvet blend recently and I have been mainlining it. It’s so good. Also check out this tea guide that Rachel Zafer and I made last year.

Cool Library of the Month

This run-down from Book Riot of most-checked-out books from public libraries in 2023 offers a fun snapshot of what people are actually reading.