Our mini Black zine fair at the Schomburg Literary Festival last month was a blast. I am now all zine-faired out for the rest of 2024. Does this mean that I won’t make any more zines this year? Of course not! I just won’t be organizing any events or tabling.

Some of you know that I cofounded a program called REBUILD a few years ago. Launched in January of 2022, REBUILD connects BIPOC formerly incarcerated individuals to therapists of color. Four part-time paid staff (including formerly incarcerated people and people who have lived experiences with mental health challenges) assist in matching formerly incarcerated and criminalized individuals with therapists of color. This assistance includes finding and vetting therapists, setting up appointments, and facilitating the payment process. Please join team members on July 10 for a virtual event to celebrate the program’s successes. Learn more about REBUILD in this newsletter.

In this month’s edition of Prisons, Prose & Protest, I share some thoughts about writer Chester Himes. I highlight my most recent Archival Activations zine about the Ohio Penitentiary Fire of 1930, I recommend a podcast episode about building communities to resist torture, several good recent articles, and much more….

Prisons/Policing

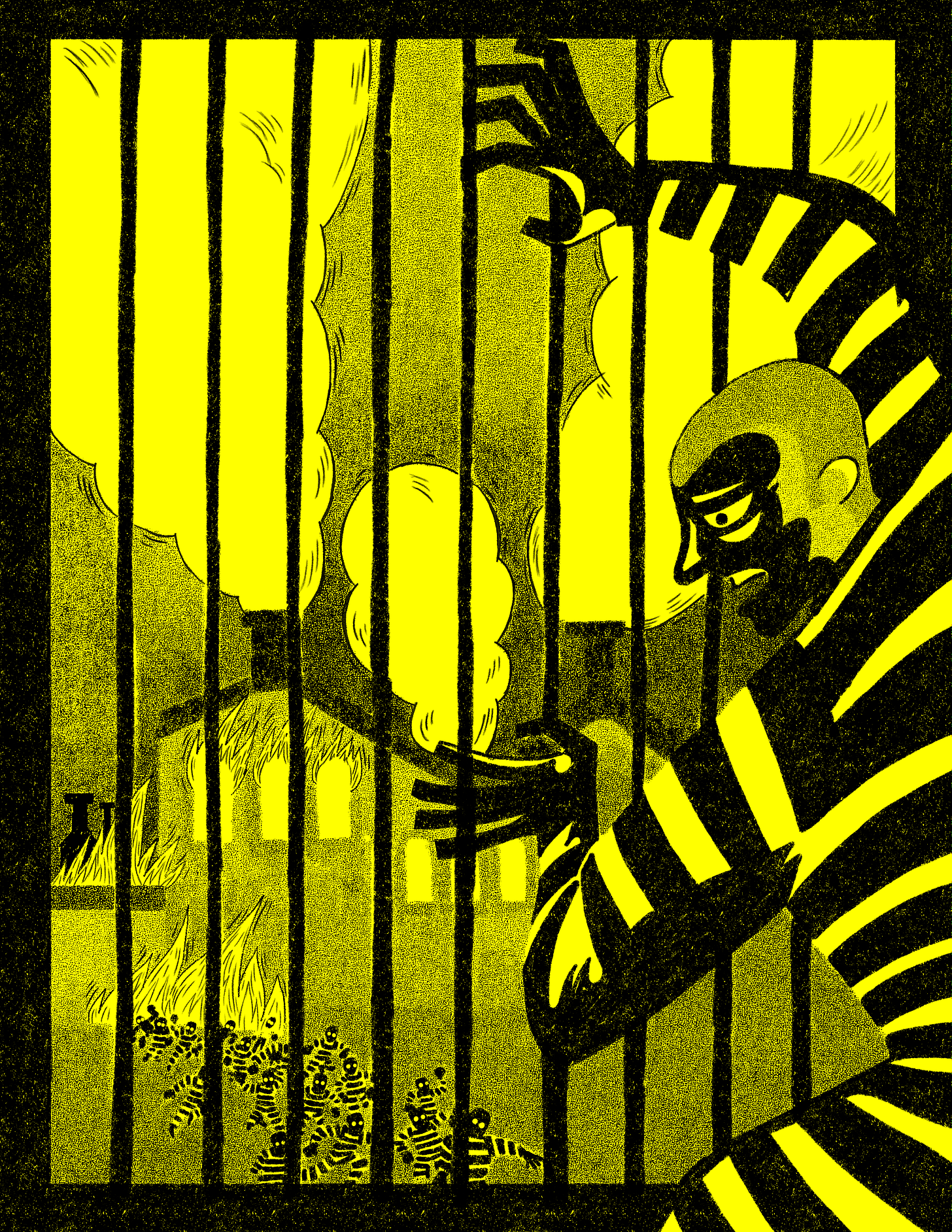

I finally read Fire In The Big House by Mitchell P. Roth, a book that has been in my “to read” pile for years. It describes the circumstances of the deadliest US prison disaster: the Ohio Penitentiary fire in 1930. I created a zine based on the incident and am excited that three wonderful artists—Kruttika Sursula, Hector “Bori” Rodriguez, and Emma Li—contributed original art to the project.

Through the book, I learned that writer Chester Himes was in prison at the Ohio Penitentiary during the fire.

“Nothing happened in prison that I had not already encountered in outside life,” Himes (1909–1984) wrote of his incarceration. But while he sometimes downplayed the experience, Himes’s time in the Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus shaped his life and his writing. Prison provided a blueprint for the depiction of violent crime and violent law enforcement in his fiction. It also underlay his bleak assessment of American life and anti-Black racism.

Himes’s father was a professor, but Black middle-class status in the 1920s was precarious. Himes fell down an elevator shaft the summer after he graduated from high school. To control the pain while at Ohio State University in Columbus, he self-medicated with alcohol and other drugs. This put him in contact with Columbus’s underworld of bootleggers and thieves.

He stole cars and quit college. In 1928, at 19, he broke into a couple’s home to steal jewelry. The police arrested him while he was attempting to pawn it. The police tied him upside down and beat his genitals during the interrogation; he confessed and was sentenced to 20 years.

About a quarter of the population of the Ohio State Penitentiary was Black, despite Ohio's Black population being only 5%. Black prisoners were segregated from white ones. Himes was one of the youngest prisoners and was also one of the few who had been to college. He was afraid of the other prisoners (“Every one of them looked big and tough,” he wrote in his 1952 prison novel Cast the First Stone) and chafed under the harsh prison rules. When he complained about the work of shoveling coal in winter, the prison authorities threw him in solitary.

After some months, and after his mother wrote many letters and advocated on his behalf, the authorities officially recognized Himes's injuries and transferred him to a cell-block for disabled prisoners. He was no longer required to work, which gave him time to read and to focus on writing.

He found his first major topic on Easter Monday, 1930, during a catastrophic fire in the penitentiary. Three-hundred and twenty-two prisoners died when scaffolding and a wooden roof caught fire. Prison guards, more focused on escape attempts than on the safety of the prisoners, dithered about unlocking the cells as men succumbed to smoke inhalation.

Himes was horrified and traumatized by the terrifying scenes of prisoners thrusting their heads in toilets in their cells to escape the smoke, by the screams for help, and by his own failure to do more to help. These experiences and emotions became the basis for his most successful early short story, “To What Red Hell,” published in Esquire with only his prison number as a byline in 1934.

The tragedy had two other major effects on Himes’s life in prison. First, the fire and its mishandling created a public backlash against prison overcrowding. The authorities implemented new parole regulations that meant Himes was eligible for release in 1936, twelve years before he’d expected to be free.

Second, the fire, and perhaps witnessing prisoners grieving for their lovers, made Himes more comfortable with his own attraction to men. In 1933, he met and began an intense love affair with a twenty-four-year-old named Prince Rico, who was incarcerated for robbery. Rico admired and encouraged Himes’s writing; the two discussed a range of influences and models, including Langston Hughes, Ernest Hemingway, O. Henry, and Black cartoonist E. Simms Campbell.

Between 1932 and his release in 1936, Himes wrote many stories and developed his craft. He published many pieces in Abbott’s Monthly, a publication created by Robert Sengstacke Abbott, who had also founded the Chicago Defender. Himes wrote stories about condemned men and prison violence. He also explored issues of racism that would become important to his later work.

After prison, Himes struggled to make a living as a writer. For a time, he lived with his cousin, journalist Henry Lee Moon, and Moon’s wife Mollie Moon in their Harlem home. For more about this experience, read Tanisha Ford’s new biography of Mollie Moon. Himes drank heavily and mistreated women in his life. Eventually Himes left the US in the mid-1950s for permanent exile in Europe. He continued to draw on his experiences inside for his novel Cast the First Stone (1952), which was republished after his death in its original form before the intervention of publishers as Yesterday Will Make You Cry (1998). His experiences with law enforcement and incarceration provided important material for his nine hard-boiled novels of Harlem crime, starting with A Rage in Harlem (1957).

Himes’s incarceration complicated and shadowed his life and his literary career. Ralph Ellison sometimes compared Himes to Bigger Thomas, the unreflective murderer in Richard Wright’s novel Native Son. The violence and nihilism of Himes’s writing put other peers—like Wright and James Baldwin—off. They also may have seen Himes in part through the stigma associated with imprisonment.

For his own part, Himes saw prisons as degrading and brutal—and as continuous with the degrading, brutal, racist society that built them. “It seemed so illogical to punish some poor criminal for doing something that civilization taught him how to do so he could have something that civilization taught him how to want,” he wrote about a prison execution in Yesterday Will Make You Cry. “It seemed to him as wrong as if they had hung the gun that shot the man.”

Publishing

I’ve shared in past newsletters that I am engaged in a multiyear project of activating my personal collections through publications. The series is called Archival Activations and you can read and download the first two zines here and here.

This year, I’ve co-created two new publications in the series so far. One recent zine, which I mentioned above, is about the Ohio Penitentiary Fire of April 21, 1930. The fire is the deadliest disaster in US prison history. Three-hundred and twenty-two prisoners died in the Easter Monday blaze, most from asphyxiation when smoke billowed into their locked cells. Kruttika did a beautiful job designing the zine and also contributed original artwork. Hector Bori Rodriguez and Emma Li also contributed art. Some copies of the zine and art are available for sale through Printed Matter.

REBUILD needs to raise $300,000 to keep offering invaluable support to formerly incarcerated and criminalized people in 2025. Given the successes of the program, one would think it would be easy to raise this modest amount. It is in fact not. It’s very difficult.

To support REBUILD’s work, I am offering a zine bundle of eight zines that I published in 2023 and 2024. Most of them are from my Archival Activations series.

I have 10 bundles available and will offer them on a first-come basis to anyone who donates at least $100 to REBUILD here.

Email your receipt and FULL MAILING ADDRESS (including apt or suite #) to jjinjustice1@gmail.com and I will put a bundle in the mail to you.

Prose

Please read and sit with and share Nabil Echchaibi’s “A Scream for Gaza.”

My friend and costruggler Andrea Ritchie and I discuss whether the state has a role in moving us away from extractive racial capitalism and toward an abolitionist future in this response for the Boston Review’s “Climate, State, and Utopia” forum.

In June, Inquest published a great explainer on the concept of abolitionist social work by the Network to Advance Abolitionist Social Work. It’s excerpted from Abolition and Social Work, the wonderful book edited by my friends and comrades Mimi E. Kim, Cameron Rasmussen, and Durrell M. Washington that came out a few weeks ago.

I really appreciate this piece by Tadhg Larabee and Eva Rosenfeld; it situates the 2023 Stop Cop City prosecutions in the context of historical USian efforts to criminalize solidarity by recasting it as conspiracy.

In this fascinating Critical Resistance interview, the wonderful Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Craig Gilmore speak with Yvonne Busisiwe Phyllis about the role of land in South African socialist movements.

My friend Sarah Jaffe thoughtfully tells the story—and reflects on the significance—of this spring’s antigenocide university encampments in In These Times. Pre-order her forthcoming book here.

James Kilgore and Vic Liu talk with Adam McGee about their innovative and informative new art book, The Warehouse: A Visual Primer on Mass Incarceration.

Podcast

This episode of Under the Tree: A Seminar on Freedom with Bill Ayers features artists and activists Aaron Hughes and Amber Ginsburg, who have collaborated on two recent books about torture, humanity, creativity, and—one of my favorite topics—tea. The conversation between Ayers, Hughes, and Ginsburg is grounded in the deep connections between US militarism abroad and the violence of US carceral systems, and in the way resistance to those systems is also interwoven.

Poem

I love the interplay of hope and loss in “Beginners” by Denise Levertov. Life is short and beautiful; while we’re here, let’s “join / our solitudes in the communion of struggle.”

Potpourri

Those in NYC should go to this July 13 book talk at Bluestockings Bookstore with Rachel Herzing and Justin Piché about How to Abolish Prisons.

Join us on August 1 for a virtual training on how to strengthen and expand public libraries. Hosted by Run For Something and For the People: A Leftist Library Project.

Retrieval is a breathtaking and moving film by Fatimah Asghar. CW: Sexual violence.

Wonderful comrade Raynise created this delicious Raspberry Riot Candle inspired by our A Riot at the UN zine. The candle is a fundraiser for Sojourners for Justice Press with 25% of proceeds going to support our work.

Saxapahaw Prison Books has a new home in Brooklyn. My comrade Moira launched the project and she needs volunteers to come read letters and pack books. Donations for mailing costs are also needed.

There’s a terrific new resource from Community Justice Exchange, co-created with Dean Spade, Jocelyn Simonson, and Zohra Ahmed. It’s called “Five Questions for Cultivating Solidarity When Responding to Political Repression” and you can access it here.

I loved the Sonya Clark exhibition at the Museum of Art and Design. It is on view until September 22. Everyone in NYC should go visit.

I really love this series of people talking about their favorite songs: here’s Chika’s. And Sky Lakota Lynch’s. And Alex Newell’s.

I made these recently without the walnuts and they were delicious.

Learn about Rita’s quilt!

Cool Library Thing of the Month

This is a great story about a clothing library pilot run by Dover (New Hampshire) Public Library. The project’s originator has really interesting things to say about the clothing library as an effort to shift norms around owning vs. borrowing.

Thank you for the sharing the poem “Beginners” by Denise Levertov. Wow. Just what I needed to keep going.

Fascinating stuff about Chester Himes, who created two of the best-named detectives ever: "Coffin Ed" Johnson and Gravedigger Jones. I'd never known all that stuff about him, particularly his queerness.