Black Zine Fair is a month away and registration to attend is now open. We need places to gather right now where we can celebrate Black art and creativity. Last year was our first year pulling the fair together and it went so well that we decided to come back for year two.

There will be over 60 Black zinemakers and several workshops at the fair. There will also be a series of virtual workshops leading up to May 3. Join us in person and/or online. We’re thrilled to be hosted again by Power House Arts; they are a great partner. We’re grateful to the individual donors who contributed and also to our cosponsoring organizations. It’s going to be a special event. Join us!

Also, I have a new children’s book, Prisons Must Fall, that will be released on April 8. It’s a project that I cowrote with my longtime friend Jane Ball and that is gorgeously illustrated by my friend Olly Costello. I’m proud of how this turned out. It was a long, winding road to publication. I hope you’ll consider purchasing a copy and/or requesting it from your local public library. The reviews so far have been great. We’ve created a webpage with additional resources.

I’m co-organizing an anticriminalization Communiversity that launches in NYC in August. Our call for workshop and course proposals is open. The deadline to apply to facilitate and teach is April 25. Please share it widely.

Giving Circle Update: In March, some of you donated $2197.09 [after fees] to the Giving Circle. I donated $2177.45 to eight projects/people. Documentation of the groups that received funds is here. Thanks to everyone who has donated in lieu of a paid subscription for this newsletter. I don’t intend to monetize this newsletter on this site, so if you want to support it, please feel free to join the Giving Circle.

In this edition of Prisons, Prose & Protest, I write about a protest at NYU in the 1970s. I recommend a podcast episode about criminalized survivors of violence, several good recent articles, and more…

Protest

If you’ve been following what’s been happening at Columbia University and other Universities across the country since October 2023, you’ve witnessed the brutal force and sanctions that have been imposed on students and faculty who have been protesting Israel’s genocide of Palestinians in Gaza. Columbia has recently been working with the authoritarian Trump regime to disappear its own former students and much more. If you’re appalled by what you’ve been seeing, you’re not alone. It’s important, however, to remember that universities have long enacted violence against their communities on campus and beyond. I want to write more about these histories but for today, I thought I would reflect on an incident in the past of New York University (NYU).

I’ve been closely following the repression that NYU’s administration has unleashed on its students and faculty over the past few months. They have enacted draconian policies against protests of Israel’s genocide of Palestinians including mass arrests and the suspension and expulsion of students.

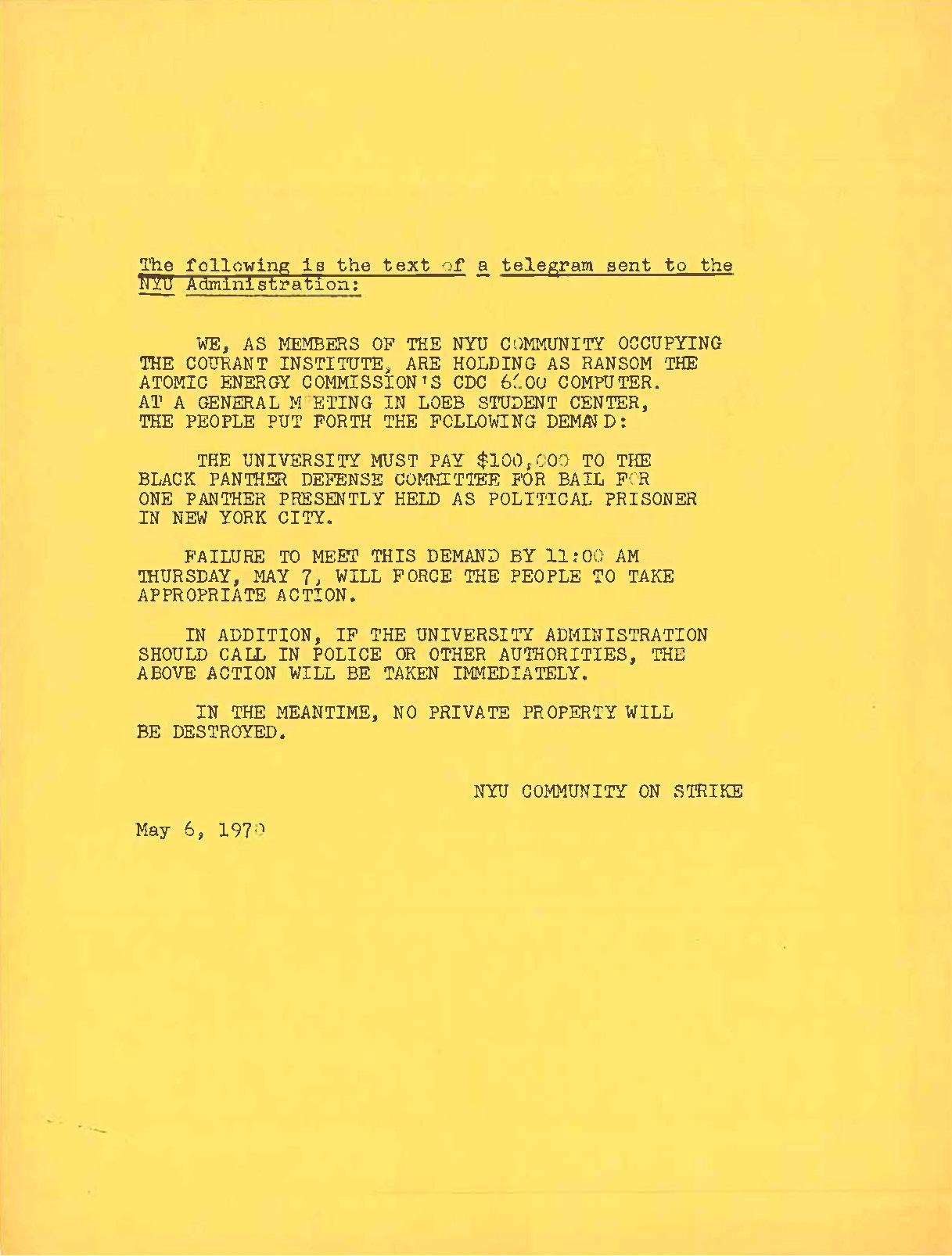

I recently came across an interesting archival document. It’s a flyer with the text of a telegram sent to the NYU administration from the NYU Community on Strike during their occupation of the Courant Institute on May 5–7, 1970. The NYU Community on Strike demanded that the University pay $100,000 to the Black Panther Defense Committee for bail for a Panther held in New York City. They threatened to destroy the Atomic Energy Commission’s CDC 6600 Computer if the administration did not meet their demands or if it called in the police.

I was interested in knowing more about this incident and am sharing what I learned with you.

The 1970 Anti-Vietnam Protests At NYU

On May 5, 1970, student antiwar protesters at New York University seized Warren Weaver Hall. a building which housed an expensive computer leased from the federal Atomic Energy Commission. Students demanded ransom and attempted to blow up the computer. Police arrested at least two students, who subsequently served time in prison.

The dramatic protests at NYU were not an isolated incident. They were part of a spontaneous, nationwide student demonstration against the Vietnam War and the policies of the Nixon administration. The NYU protests also linked the war abroad to racist policies at home, and attempted to force the administration to take a stand against both.

May 1970 Nationwide

Protests against the unpopular Vietnam War were common and ongoing by 1970. However, they sped up after President Richard Nixon announced on April 30 that he had secretly invaded Cambodia.

Nixon had promised in his 1968 campaign to end the war. Now he seemed determined to expand it. Outraged, the students were determined to push back. Protests began immediately. Activists met in New Haven and suggested a national student strike. Students at Brandeis University established a strike headquarters to coordinate protest and information.

The student movement was further galvanized on May 4, when National Guardsmen opened fire on student protesters at Kent State University in Ohio, killing four people and injuring nine others.

The murders led to an acceleration of what were essentially spontaneous, and instantaneous, demonstrations. Brandeis served as a clearinghouse for information rather than as a central planner, and there was little preparation. The Moratorium on the War in Vietnam organized for months to coordinate protests in 1969. Students launched the much larger protests of 1970 in a matter of days.

By mid-May, there had been protests in every state except Alaska, and the protests had swept 900 campuses. Over 100 campuses shut down for at least a day; twenty-one were closed for the rest of the school year. Students and police clashed violently at 26 schools. Protestors targeted the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) on their campuses, and 30 buildings housing ROTC programs were burned or bombed.

May 1970 at New York University

Like students nationwide, students at NYU were galvanized by Nixon’s address and the shootings at Kent State. On May 4, the day of the Kent State shootings, student strikers occupied NYU’s Washington Square campus student center. The next day, hundreds of striking students occupied Kimball Hall and Warren Weaver Hall.

Warren Weaver Hall held the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences and the computer leased from the Atomic Energy Agency. The computer was worth about $2 million, or some $16.2 million in 2025 dollars. Mathematician Peter Lax, the director of the computer center at the time, said in a 2015 interview that he believed that the computer was the most valuable thing on campus.

The computer had no direct military links, but students viewed it as a symbol of nuclear power, nuclear weapons, and US warmongering. The strikers demanded the NYU administration give $100,000 to the bail fund for the Panther 21, the 21 Black Panther leaders arrested in 1969 for allegedly plotting to bomb police stations. (In May 1971, a jury acquitted the Panthers after concluding that police infiltrators had incited and organized most of the bombing campaign.)

The NYU administration refused the ransom demand, and the protestors abandoned the building on May 7. Before they left, they rigged explosives to try to destroy the computer. They also removed doorknobs to prevent access to the computer rooms. Two assistant professors saw a fuse burning through a window and sprayed a fire extinguisher under the door to douse the flame, preventing an explosion which could have caused a great deal of damage in a mostly glass building.

The student movement ended in the summer, and protests [mostly] did not resume in the fall. Police arrested two people in connection with the NYU protests: Assistant Professor Robert Wolfe and graduate physics Teaching Assistant Nicholas Unger. They were each sentenced to three months in prison and lost their positions at NYU.

“We thought it was important to do as much as we could to register that protest, and that’s what we did,” Wolfe said in an interview with the New York Times in 2015. Unger agreed: “What do I say about being part of a generation of protests? The war was wrong, and people who tried to stop it were doing the right thing.”

Goals and Outcomes

Strike headquarters at Brandeis in early May issued three demands. First, they called on the US government to “release all political prisoners,” including members of the Black Panther party. Second, they demanded that the administration end its expansion of the war into Laos and Cambodia. And finally, they said that universities should “end their complicity with the U.S. war machine by an immediate end to defense research, ROTC, counterinsurgency research, and all other such programs.”

Strikers at New York University addressed each of these goals. They attempted to force the university to contribute to liberating political prisoners. They called for an end to the war. And they targeted the computer as a symbol of the university’s complicity with, and reliance on, the federal government.

The national protests forced many universities to close ROTC programs. However, the demonstrations, including the ones at NYU, did not immediately achieve their broader goals. The war did not end, and the university did not contribute to bail for the Panther 21.

Nonetheless, the national mobilization was a breathtaking demonstration of dissent and helped to keep national attention focused on Nixon’s decision to expand the war. At NYU in particular, the protests also powerfully linked antiwar demonstrations, racial justice, and a call for universities to embrace the moral values they claimed to champion. The linkage of domestic and foreign policy, and the focus on the connections between the university and the government, would resonate in future protest movements, most recently in the pro-Palestinian and antigenocide demonstrations of 2024.

Prose

This was a stunning piece of writing. You can listen to the audio version of the story even without a subscription to the New Yorker.

This op-ed by Achille Mbembe and Ruth Wilson Gilmore places the administration’s targeting of South Africa into the broader context of Trump’s international politics of cruelty and white grievance.

Read this brief history of anticarceral organizing against gendered violence by Emily L. Thuma, adapted from Thuma’s book All Our Trials: Prisons, Policing, and the Feminist Fight to End Violence.

This is a good look at how pro-Palestine campus organizers are facing down the violent repression against them by their universities, law enforcement agencies, and the federal government.

The letter that political prisoner Mahmoud Khalil dictated to In These Times from jail is a defining document of our times.

For Justseeds, Saiyare Refaei interviews Awni Farhat about his organization, the Palestinian Humanitarian Response Center (PHRC), which provides mental health support and trauma relief to young people in Gaza.

This essay by Yasmin Nair asks important questions about the “list of innocents” in the famous “First They Came For” poem, and invites us to move beyond the impulse to separate deserving from undeserving.

For Public Books, Amna A. Akbar talks to Silky Shah about Shah’s book Unbuild Walls: Why Immigrant Justice Needs Abolition, and about her work as executive director of Detention Watch Network.

The Progressive has important historical context for the Trump administration’s activist-deportation strategy.

Read Jennifer Dines’s heart-rending essay about what it feels like to be a Boston public school teacher whose recent immigrant students, along with their families and communities, are the targets of the Trump administration’s political violence.

This is a clear-eyed look at how perilous the ongoing escalation of US detentions and disappearances is. “The danger of our current political moment is the inevitable outcome of accepting and internalizing dehumanizing narratives about people we deem ’others.’”

I absolutely love this chronicle of one couple’s successful efforts to introduce a weekend “stoop coffee” community practice into their neighborhood.

Podcast

Survived & Punished NY has a wonderful new podcast! Each episode of Survivor Chronicles: Free Them All tells the story of a survivor criminalized and incarcerated by the state of New York. The show notes contain further resources and calls to action connected to S&P NY’s mass clemency campaign.

Poems

Joanne Kyger’s “[I want a smaller thing in mind]” is, I’m guessing, deeply relatable for all of us right now.

Potpourri

I spoke with my good friend and comrade Kelly Hayes about organizing in our current moment.

4/17 - Join For the People for our People’s Assembly Toolkit launch event to learn about our new resource for holding facilitated community gatherings about library issues.

4/19 - Black Women Publishing and Material Culture at The Free Black Women’s Library in Brooklyn - 3 to 5 pm ET.

4/27 - Are you seeking a space where you can reflect individually and with others on your ongoing activism and organizing? If yes, join me on April 27 for an Activist Drop-In Space. I’m holding one the last Sunday of every month through December on Zoom from 4 to 6 pm ET. This is for people already engaged in some form of activism and organizing. Space is limited. Please only sign up if you are sure you can drop in.

Please spread the word about the Keeley Schenwar Memorial Essay Prize. It is awarded every year by the Truthout Center for Grassroots Journalism to two writers who are currently or formerly incarcerated, and the deadline for submissions is May 20.

I really love this new zine by Violet B. Fox: Radical Books That Aren’t a Slog: Leftist Book Recommendations for Newly Radical Folks.

This is a beautiful and fascinating project.

Digital Schomburg has put out a “dual-publication, digital flipbook and limited edition printed zine” called In Them We All Exist: Reflections and Resources on Black Lesbian Herstory in the Archives.

Season 7 of the PBS/WTTW documentary series Firsthand profiles Chicago residents who spend their time peacekeeping and community-building in various ways.

Watch Sojourners for Justice Press’s YouTube short, Paper Trails From the Archives: The Black Women Targeted in Red Channels,

I highly recommend this episode of PBS’s American Masters about jazz musician and TV host Hazel Scott.

Cool Library Thing

I love this experimental Stacks Explorer tool for the Prelinger Library in San Francisco. “This project arose from a series of questions … about how a library website might function if it prioritized looking rather than searching, and how a library without a formal catalog might surface its holdings to offsite patrons.”

As a Brandeis alum, appreciated the bit of Brandeis radical history. Black Brandeis students at this time also occupied Ford Hall, renaming it Malcolm X Hall, as part of their campaigns for university changes. Also, let's reconnect soon! I'm still in NYC.

Fascinating read!