Prisons, Prose & Protest - #35

Rants, Musings and More

I love February because it’s Black History Month. I always learn something new and find new rabbit holes to fall down.

It’s a busy month for me with a few public events, many meetings, and more. Dr. Jeanne Theoharis and I are in conversation this Tuesday February 3rd at 6:30 pm about her excellent book “King of the North: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Life of Struggle Outside the South.” Join us in person or via Livestream.

On February 10, I am moderating a conversation at the Center for Brooklyn History about how storytelling and art can lead impacted people and larger society to rethink the systems within the criminal legal system. The event is a celebration of the launch of Letters from Home and will include readings by several poets and writers. The event is free and open to the public.

In this edition of Prisons, Prose & Protest, I share information about the first Black bookstore in the United States. I recommend a couple of podcast episodes about the inspiring organizing happening in Minnesota, several good recent articles and essays, and more…

Last year, I blurbed Char Adams’s engaging and informative book Black Owned: The Revolutionary Life of the Black Bookstore. The book offers the first comprehensive history of Black bookstores in the US. One of the bookstores that Char features is D. Ruggles Books, the first Black bookstore in the US.

The First Black Bookstore in the United States: D. Ruggles Books

“Knowledge unfits a child to be a slave,” self-emancipated abolitionist Frederick Douglass wrote. It wasn’t just abolitionists who believed that knowledge was a powerful tool against bondage. Slaveholders also believed that their grip on power depended on keeping Black people in ignorance—which is why the man who enslaved Douglass was dead set against him learning to read.

If illiteracy was a key form of oppression, then books were a pathway to freedom. No wonder, then, that Black-owned bookstores have been a central rallying point for Black resistance throughout US history. That resistance started with the very first Black-owned bookstore in the country, D. Ruggles Books, established in New York in 1834 by one of the country’s most courageous and uncompromising abolitionists, David Ruggles.

The Growth of a Radical Bookseller

Ruggles was born the first of eight children in 1810 to a free Black family in Connecticut; his father was a blacksmith and his mother was a well-respected cook. He got an education and learned to read at a religious charity school. David grew up in an integrated community that strongly supported abolition. He went to school with white children and had many white friends.

In 1826, at sixteen, Ruggles moved to New York City. He initially worked as a mariner; then, in 1828, at the age of 18, he opened a grocery store at 1 Cortlandt Street in lower Manhattan. He initially sold liquor, but soon took up temperance and swapped the alcohol on his grocery shelves for something more intoxicating.

Ruggles didn’t stock just any books; he sold abolitionist pamphlets and literature. He also employed two brothers who had escaped slavery, and he supported the free produce movement, boycotting goods made with the labor of enslaved people. He placed advertisements in the first Black-owned newspaper in the country, Freedom’s Journal. Even though his store was not in a heavily Black area, his integrity, business sense, and passion for abolition made the store popular, and he had customers from throughout the city.

But successful Black businesses, and especially defiantly abolitionist Black businesses, were targets for white violence. In 1829, someone broke into his store, stole $280, and set the building on fire. It was not the last time that white racists would attack Ruggles’s businesses.

Ruggles, however, persisted. He turned to abolition full time, becoming one of the few Black agents for the antislavery paper The Emancipator. He traveled throughout the Northeast to give abolitionist speeches, meet with publishers, and encourage subscriptions.

In 1831, Nat Turner led a slave revolt in Virginia in which Black revolutionaries killed 55 white people. Authorities soon captured and executed Turner, but fear gripped white people across the country. Many blamed David Walker’s militant abolitionist Appeal, published in 1829, which Turner probably hadn’t read, as well as the Bible’s antislavery passages, which Turner knew inside and out.

In response to Turner’s rebellion, slavers cracked down on Black literacy. Virginia outlawed teaching free Black people reading or writing; other states quickly followed. In 1833, a white student in Tennessee was publicly whipped for carrying abolitionist literature.

D. Ruggles Books

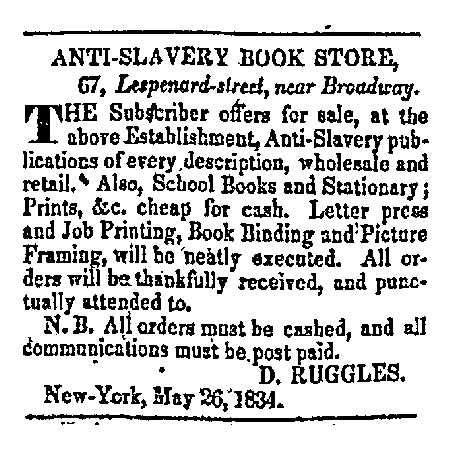

Abolitionists and Black people refused to be intimidated, however. In 1831, William Lloyd Garrison launched The Liberator, which quickly became the leading abolitionist paper. And in that same year, Ruggles opened another store—this time devoted entirely to books. Historians believe that Ruggles’s business, situated at 67 Lispenard Street in what is now the Tribeca neighborhood, was the first Black-owned bookstore in the country.

Ruggles’s store was promoted in both The Liberator and The Emancipator. It sold stationery and paper—but it specialized in abolitionist pamphlets and the occasional book such as Lydia Maria Child’s virtually banned antislavery book The Oasis. Ruggles also had his own press, and published and sold his own pamphlet, The Extinguisher, which meant that he had the first Black-owned imprint in New York.

White racists targeted Ruggles’s new stores just as they had his first. An 1835 public notice referred to the store as an “incendiary depot” and called for Ruggles to be lynched. Soon afterwards, a mob burned down his office, which was next to the bookstore. White racists then sat outside the store for three nights to intimidate Ruggles and his patrons.

Ruggles responded by condemning the attacks. He offered $50 for any information leading to the conviction of the arsonist and $25 for anyone who could identify members of the mob outside his office. No one came forward to claim the money, but it was almost unprecedented for a Black business owner to even attempt to hold a white mob to account.

Nor did Ruggles close his store. He even expanded, adding a reading room and a lending library. The reading room served, in Ruggles’s words, as a “centre of literary attraction for young men whose mental appetites thirst for food.” He hoped it would keep Black youth from vice—by which he probably meant drink, given his temperance commitments.

Even though most libraries banned Black people, Ruggles insisted they deserved “access to the principal daily and leading anti-slavery papers, and other popular periodicals of the day.” Ruggles Books became an oasis of African American learning, community, and organizing in a city where white people were fiercely opposed to all three.

There was a fee to join Ruggles’s reading room, but he said that “strangers visiting the city can have access to the Reading Room, free of charge.” This was meant to ensure that those who had escaped from slavery could use the space.

Beyond the Bookstore

Ruggles’s commitment to abolition went well beyond selling pamphlets. He was a one-man whirlwind of activism and emancipation. His home was a central stop on the Underground Railroad in New York City, and he helped 600 to 1000 people in their escape from slavery.

Among those he aided was Frederick Douglass, whom Ruggles reunited with Douglass’s fiancée, Anna Murray. They were married in Ruggles’s home; he also gave them money and urged them to settle in the port city of New Bedford, Massachusetts, where there was a thriving free Black community and where Douglass, a caulker, could find work. Douglass later described Ruggles as “a whole-souled man, fully imbued with a love of his afflicted and hunted people.”

In 1835, Ruggles helped found, and served as secretary of, the New York Committee of Vigilance, which aided fugitives from slavery. He was at the forefront of the fight against bounty hunters who illegally kidnapped Black people in the North and sold them in the South. Ruggles fought to secure jury trials and legal representation for victims. He also went to investigate cases of people illegally held as slaves in supposedly free New York and would personally escort them to safety. Not satisfied with these exertions, he launched his own publication, The Mirror of Liberty—the first Black-owned magazine in the US.

Ruggles was a leading advocate of armed resistance to kidnappers when necessary. That position made him a pariah even among many abolitionists and it enraged white racists. Ruggles was himself the target of multiple kidnapping attempts. At least once, a constable arrested him, likely intentionally “mistaking” him for an escaped slave.

Frederick Douglass said that when he first met Ruggles in 1838, Ruggles was “watched and hemmed in on almost every side,” but that “he seemed to be more than a match for his enemies.” This was, unfortunately, wishful thinking. Ruggles suffered from sickness and failing eyesight; by 1841 he was virtually blind. He moved to Florence, Massachusetts, for his health in 1842. It is not clear exactly when he closed his bookstore, but it must have been shuttered by the time he left the state.

Distant from New York and unable to see, Ruggles could not continue to pursue his abolitionist work with the same intensity, though his instinct for business opportunities remained strong. He started one of the first water cure hospitals in the US during the 1840s. He died in 1849 of a bowel infection at the age of only 39.

Legacy

People do not know Ruggles as well as they know abolitionists like Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Sojourner Truth. However, in recent years, his importance has become increasingly recognized. His combination of militant activism and radical commitment to education has served as a blueprint for generations of Black organizers, leaders, and booksellers.

“When tracing the life and history of Black bookstores in the United States, all roads lead back to Ruggles,” Adams writes in Black-Owned: The Revolutionary Life of the Black Bookstore. She adds:

“It’s been almost two hundred years since Ruggles opened his little anti-slavery bookshop in Manhattan, but it hasn’t ever really closed. It’s existed over and over through the centuries in the Black bookshops that have dared to position themselves as radical spaces, ones dedicated to the uplift and liberation of Black people.”

For Ruggles, freedom meant free access to knowledge, and knowledge was inseparable from the work of freedom.

Publishing

I currently have four 2025 zines that are only available as hard copies at Printed Matter:

Charles Ray and the New York Committee of Vigilance by Mariame Kaba, designed by Tash Nikol of Grace Issues Press (2025) - Archival Activations #9

Blocking Traffic: A Brief History of Road Closures as Protest by Mariame Kaba, designed by Cindy Lau (2025) - Archival Activations #10

The Fifth Street Building Takeover by Mariame Kaba, designed by Kruttika Susarla (2025) - Archival Activations #11

The Black Woman’s Bill of Rights: A Manifesto by the National Alliance of Black Feminists by Mariame Kaba, designed by Ann-Derrick Gaillot (2025)

Prose

This Deborah Chasman interview with Robin D. G. Kelley situates the murder of Renee Good (and implicitly the murder of Alex Pretti, which occurred after it was published) within the long US history of police murders.

A tapestry of stories and commentary from Minnesotans—snapshots of what it looks and feels like to live through, and protect each other from, a violent federal siege.

Margaret Killjoy visited Minneapolis and reports back with her typical care and acuity on the decentralized, hyperlocally based, leaderful movement she observed there.

In Truthout, Minneapolis organizers Jonathan Stegall and Anne Kosseff-Jones reflect on how abolition—and Minneapolis’s history of building toward it—shows up in the current moment of anti-ICE mobilization there.

Erin West gives a personal account of what it feels like to confront federal agents in the streets alongside an entire city: “Ice vs. Everyone.”

My friend and comrade Holly Krig reminds us how to move in solidarity in this moment: “Abolitionist co-strugglers have …always known that it’s not about guilt or innocence, dangerousness, or all the other claims systems make. Militarized borders and heavily gated pathways to citizenship ensure a permanently exploitable class, much like felony convictions.”

Silky Shah’s analysis is critical to understanding the crisis of anti-immigrant and racist violence we’re in; here, she walks us through the terrifying build-ups of an already-robust deportation infrastructure that have brought us to this moment.

In Nonprofit Quarterly, my friend and comrade Dean Spade talks about one of his areas of expertise: how to move through conflict in movement spaces.

A great article by Astra Lincoln about what cost-free and surveillance-free health care can look like, and about Love Heals, a pop-up, philanthropy-funded clinic dedicated to providing it.

This excerpt from Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s new introduction to How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective is a must-read, as is the new edition of the book itself.

Podcast

Two terrific podcasts have released important dispatches from occupied Minneapolis.

Poem

I’m embracing Diane di Prima’s “REVOLUTIONARY LETTER #100: REALITY IS NO OBSTACLE” as an instruction manual this month.

Junauda Petrus’s “Ritual on How to Love Minneapolis Again” was read a year ago during the announcement that Petrus would be the city’s poet laureate for 2025 and 2026. But the poem somehow tells so much of the story of Minneapolis in the current crisis; of the community connection and rich culture that have become central to the city’s rejection of state violence.

Potpourri

Black Zine Fair 2026 — the application for exhibitors, workshop facilitators, and volunteers is due next Monday, February 9.

February 12, 6:30–8 p.m. ET - Accountability Beyond Punishment Workbook, a virtual session on transformative justice with organizer and transformative justice facilitator Camila Pelsinger Villalba. This session is for people who are practicing or curious about transformative justice, survivor support, and community-based responses to harm—no prior experience required. Registration is free but only sign up if you know you can attend. The session will not be recorded.

Haymarket Books has made three of its excellent titles free as ebooks, so we can all read and think together about migrant justice and border abolition.

February 19, 6:30–8:00 p.m. ET - For the People Leftist Library Project is organizing an open house for people who are interested in joining their local Friends of the Library or Library Foundation group—or are already involved in some way. The purpose of the event is to provide a space to come together and share resources and strategies on how to be an active and effective participant in such a group.

The Samora Pinderhughes: Call and Response exhibition at the MOMA runs through February 15, with several connected performances, and you should go if you are in New York City and able. It uses film, sound, and performance to ask, “What if we built a world around healing rather than punishment?,” from the perspective of an artist who has been working on that question for a long time.

My friend and comrade Monica Trinidad has such a powerful way of talking and teaching about art for social movements.

A true Lego master.

I have been battling various colds and so have been guzzling dawa (lemon, honey and ginger tonic). This is an immune-supporting tonic that is great to keep flus away or manage their symptoms well. Here’s a recipe.

Cool Library Thing of the Month

I loved this interview with a public middle school librarian in San Francisco who is hoping to use vinyl records collected from neighbors and an inherited record player to draw students into analog music listening. I love her drive to expose middle schoolers to the context around artists and music cultures that comes with listening to music in album form.

An incredible amount of history and resources. Thank you for your life-giving work.

I love Mon Rovia! Thank you for including his music in your newsletter.