Welcome to my personal newsletter! In this issue, I talk about archives and the carceral state. I share another new zine. I recommend a couple of recent podcasts that I appreciated and much more. If you like the newsletter, please feel free to share it with others. Happy reading!

In peace,

Mariame

P.S. Shreya Chattopadhyay over at the New York Times recommends Let This Radicalize You as one of 6 paperbacks to read this week! Have you picked up your copy yet? It’s currently 40% off from Haymarket.

Prisons/Policing

I went back to school a couple of years ago to study library and information science with a particular focus on archives and archiving. I completed my Masters in Library and Information Science (MSLIS) last December. As part of my coursework, I spent a lot of time thinking about the intersections between archives and social justice.

Archivists who root their practice in social justice underscore that archives are both sites of important memory work and also of oppression and violence. Archivist and scholar Michelle Caswell has critiqued mainstream institutional archives for engaging in the “symbolic annihilation” of marginalized people. Writer Hugh Ryan points out that “archives are always biased. We often assume that they are a kind of neutral record, but people enter into them as subjects on terms that are often not their own.”

Still, archives do frame knowledge and very much shape collective memory. Marginalized groups are acutely aware of this. Over the past few decades, many who were previously excluded from institutional archives have sought to create their own to document their lives and insert themselves into history. In 1979, Black feminist scholars and organizers Barbara and Beverly Smith gave voice to this practice:

One thing we know as Black feminists is how important it is for us to recognize our own lives as herstory. Also as Black women, as Lesbians and feminists, there is no guarantee that our lives will ever be looked at with the kind of respect given to certain people from other races, sexes or classes. There is similarly no guarantee that we or our movement will survive long enough to become safely historical. We must document ourselves now.

According to this framing, documentation can be seen as a form of activism. This kind of “archiving from below” allows for parts of marginalized people’s lives to be made more visible to themselves in the present and to others in the future.

Over the past decade, I’ve been thinking a lot about the intersections between archives and the carceral state. Some scholars posit that the carceral state essentially describes “policies, practices, ideologies, economies, and structures that punitively scrutinize individuals and communities before, during, and after contact with the criminal justice system.” I like a definition of the carceral state that was offered by my friend Dr. Erica Meiners:

Carceral state refers to the multiple and intersecting state agencies, institutions, and associated not-for-profit organizations that have policing and punishing functions and effectively regulate poor communities, including those beyond the physical site of the prison or jail: child and family services, welfare/workfare agencies, immigration, health and human services agencies.

This summer, I am co-organizing and co-facilitating a Youth Public History Institute (YPHI) for young people ages 16–24 in NYC. The institute kicks off on July 10. I’ve been working on the curriculum and a significant part of the program includes discussion and consideration of archives and archiving. Program participants will visit a couple of repositories to learn more about the histories of prisons, policing, and surveillance in NYC. It’s important to me that young people be exposed to primary source materials and learn how to use them to tell stories of their past, present, and future. This feels even more relevant amidst current reactionary and authoritarian efforts to suppress specific information, knowledge, and histories.

My former LIS classmate and comrade Sarah Cuk has been working with me to plan the curriculum. She has created an invaluable resource that we will be using this summer: A LibGuide for Researching the History of Police, Prisons, and Surveillance in NYC. I am sharing the guide publicly for the first time in this newsletter. We invite feedback on it from archivists, librarians, educators, students, and organizers. It is a dynamic resource and a work in process. This LibGuide is explicitly rooted in an abolitionist praxis for encountering the archives. (Relatedly, after a few years away from classroom teaching, I am slowly developing a college-level course focused on archives and the carceral state. Not sure when or where I will teach it yet, but I hope to in the coming years.)

There are other resources we are currently developing for the program that we hope to make publicly available after this summer. Our goal is to share what we make and to learn from others. Please reach out to me if you want to replicate the YPHI in your city or town in 2024 or beyond. I will be happy to share information about what we do this summer. The YPHI is made possible by the generous support of the Mellon Foundation and Project NIA’s donors.

Publishing

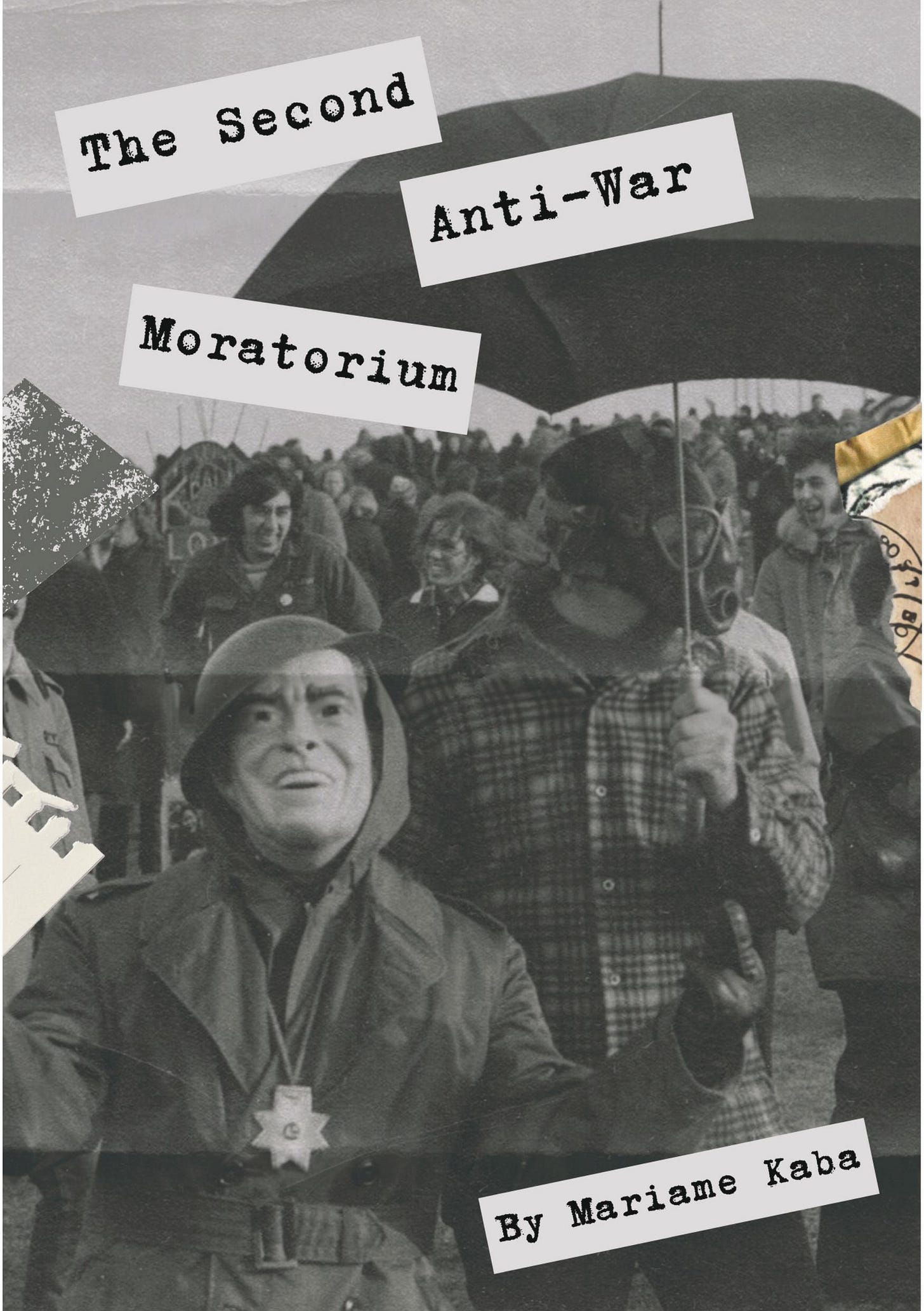

New Zine Alert - The Second Anti-War Moratorium: October–November 1969

In 2022, I purchased a set of photographs and a brochure from Division Leap about the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam mobilizations and actions that took place in October and November 1969. On November 15, 1969, 500,000 people marched on Washington in what was billed as the Second Moratorium Against the War in Vietnam. Smaller marches were also held in cities across the country. The mostly peaceful demonstration was believed to be the largest antiwar protest in United States history at the time. With research support from Noah Berlatsky and graphic design by Andrea Kszystyniak, this zine tells a story of these antiwar mobilizations.

The publication is the second in my Archival Activations series. Using my personal collections, I feature specific documents and records and provide historical context. The first zine in the Archival Activations series, released in April, was focused on abortion and medical violence.

You can read the new zine here.

I’m excited to continue my Archival Activations series. I hope to publish one more zine in the series before the end of 2023.

Podcast

Yohance Lacour, a Chicagoan and formerly incarcerated writer, narrates a seven-part podcast series titled You Didn’t See Nothin, which explores the 1997 racist attack on Lenard Clark, a 13-year-old Black boy. This podcast works because it weaves together memoir, history, and investigative reporting. If you’re from Chicago, you’ll also appreciate how the politics and complexities of Chicago are covered. Even though I was living in the city at the time of this incident, I learned many new things about it. I was riveted throughout the entire series.

I also recommend Blind Plea, a podcast by Liz Flock telling the story of Deven Grey, a Black woman charged with murder after shooting her abusive white boyfriend. Grey was offered and accepted a “blind plea,” in which she pleaded guilty without knowing what sentence she would receive. The podcast looks at Grey’s case in terms of criminalized survival and the dynamics of race and gender in the criminal punishment system. I appear in Episode 4 discussing perceptions of Black women survivors and arguing that laws like Alabama’s Stand Your Ground law will never protect victims like Deven Grey. Deven is now out of prison and needs resources to support her re-entry. Please contribute here if you can.

Prose

The American Prison Writing Archive (APWA) is an excellent resource that includes over 3,500 essays by currently incarcerated authors, searchable by keyword, state, prison facility, author background, and more. Over 400 prison facilities and 1,000 authors are represented in the archive, which grows by up to 70 essays each month. The APWA website describes its commitment to lifting up incarcerated voices:

The Archive is built on the belief that incarcerated people are always the leading experts on practices and policy of legal confinement’s effects. They can offer a generative index of state and civil society’s (mis)managing of criminal legal systems and public safety. APWA writers are spokespeople for the challenges, aspirations, hopes, and enduring resistance and resilience of imprisoned people.

I recently read a paper titled “Activist Bibliography as Abolitionist Pedagogy in the American Prison Writing Archive” by Kirstyn J. Leuner, Catherine Koehler, and Doran Larson. The authors describe two cases where university instructors assigned their students to participate in the APWA as “citizen archivists,” transcribing and contributing metadata to the entries. The paper explores the transformative possibilities of this model, where the students both learn from and contribute to the digital archive, making the classroom into a site of solidarity.

Poem

This month, I want to share the poem Sometimes by an author who no longer wishes to have her name associated with it. I like to think about the conditions that foster the "sometimeses" she describes. What role can I play in melting "a field of sorrow / that seems hard frozen"? I draw energy from the promise of the “sometimeses,” and I hope we can all continue working to build the conditions that invite them in.

Potpourri

Fundraising - I am working to raise a much-needed $50,000 for the Online Abortion Resource Squad (OARS). Will you help me reach my goal? We are less than $2,000 away. If you are able and interested, any amount is welcome. OARS does critical work, using a peer-based online counseling model to ensure that people looking for online information about abortion are connected to the resources and facts they need.

Queer Portraits in History - Since 2014, illustrator Michele Rosenthal has been drawing bright, compelling portraits of queer historical figures and posting them online alongside biographical info about each subject. There are currently 96—with subjects ranging from labor organizer Pauline Newman to choreographer and voguing pioneer Willi Ninja—and Rosenthal adds portraits regularly. Share this with others during this Pride month and beyond.

Please watch this short film about Trina Reynolds-Tyler and the work she does to deepen community understanding of gender-based police violence through the Beneath the Surface project. Beneath the Surface, which is based in Chicago, “uses machine learning and narrative justice to better understand how marginalized communities experience police violence.” The film is by cai thomas and was released as part of PBS Independent Lens' Bridge Builders series.

Join me and co-facilitator Geoff Johnson on July 23 at 4:00 PM EDT for the fourth 2023 session of our Intergenerational Reading Group focused on the life stories of antislavery abolitionists. This month, we’ll be reading about and discussing Shields Green. This virtual, bimonthly reading group is open to anyone 15 years old and up. Register here.

Go visit Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration if you’re in NYC - The New York Public LIbrary’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture is hosting this beautiful exhibit through early December. Curated by Dr. Nicole R. Fleetwood, it uses works by 40 artists—many of them currently or formerly incarcerated—to uncover truths about the carceral state.

Dessert - These are delicious, and, critically for this July newsletter, don’t require you to turn the oven on.

My forthcoming guidebook Lifting As They Climbed with Essence McDowell will be available in August through Haymarket Books.

Cool Library Thing of the Month:

Libraries and Lemonade—For the People: A Leftist Library Project is encouraging everyone to set up free lemonade stands this summer as a cooling and delicious way to engage your neighbors in conversations about the importance of public libraries.