Welcome to my personal newsletter! Thank you for reading. In this issue, I discuss a fascinating 19th-century antislavery and anti-prison abolitionist and write more about the prison censorship exhibition I curated. I recommend a podcast episode I enjoyed, share my birthday fundraiser benefitting REBUILD, offer ways to support the demand for a ceasefire and end to occupation in Palestine, and much more...

To begin, millions around the world are calling for an immediate cease fire and an end to the occupation. I invite you to visit bit.ly/StopGazaGenocide to learn more about how you can take action today, and gazaispalestine.com to find an upcoming protest near you. Kelly Hayes and I offered this excerpt from Let This Radicalize You published at TruthOut a few weeks ago for those interested.

I’ve been politically committed to a #FreePalestine for as long as I can remember. As my parents were before me. Palestine WILL be free.

Return to Sender will close on Saturday October 28, so if you haven’t had a chance to stop by yet, this is the week to do so! We’ve had hundreds of visitors. I’ve loved the conversations that the exhibition has sparked and I hope that it will also catalyze action(s). There were a couple of wonderful articles about the exhibition published this month here and here.

And yes, I’m already planning my next exhibition, LOL. Hopefully in 2025 or 2026.

My comrade Dr. Garrett Felber, who was an essential thought partner and adviser for Return to Sender, suggested that I include an exhibit inspired by Faith Ringgold’s 1972 work titled The United States of Attica.

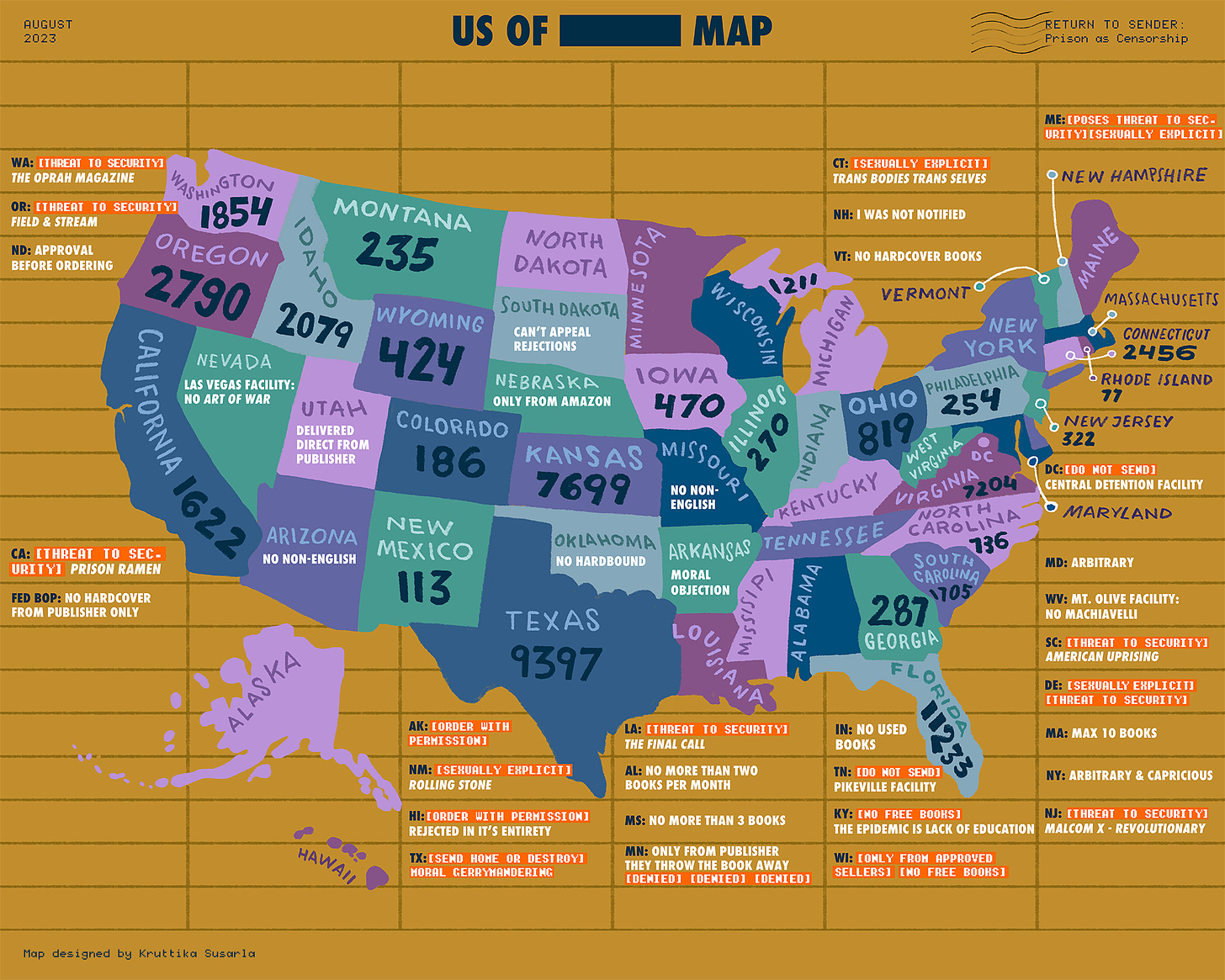

The United States of [Redacted/Redaction] Maps offer a snapshot of carceral censorship across the fifty states. I invited three artists to offer their interpretations inspired by Ringgold’s work. Using data from PEN America, Danbee Kim, Pablo Mendoza, and Kruttika Susarla created artistic representational maps of book bans in US prisons.

The data on the maps is incomplete because many state and federal prisons do not report some kinds of rejections. For example, if someone is mailed a book but doesn’t get the warden’s permission to receive it in Georgia, the staff does not file paperwork for the rejection. The incarcerated person is given two options: pay to mail the book to a home address, if they have one, or allow it to be trashed. If Texas bans a book, the staff will make the decision to either mail it to a home address or dispose of it and no additional documentation is required.We can never know how many books are not delivered based on the predilections and biases of staff, one of the many reasons the true number of censored books in prisons is unknown.

We are selling prints of Danbee and Kruttika’s maps to raise money for REBUILD, which connects formerly incarcerated people to free mental health services. The maps are $35 including shipping and handling. You can directly donate $35 to REBUILD and then email jjinjustice1@gmail.com with proof of donation & full mailing address to receive your map.

Prisons/Policing

While curating Return to Sender, I had an idea to create an exhibit of works by incarcerated writers, including poetry, novels, and letters. I decided against this because of the volume of published writing by incarcerated people that exists. How would I decide what to include? I could limit myself to materials written in English, focused on experiences of imprisonment, and published in the United States. This would still be a huge corpus of materials to share in a single exhibit. Besides, Harvard's Houghton Library held an exhibition earlier this year called Sentences: Prison Writing through the Ages. It displayed works from over fifty authors from different eras and different parts of the world who wrote about their incarceration from prison or after being released. Harvard Magazine spoke to the curator about the exhibition.

I’ve always been interested in people who became writers through their experience of incarceration. I’ve been collecting works by such authors for many years. This link lists some of the books and items in my collection. I would like to catalog the entire collection, but it’s a work in progress and it might never be complete. Shout out to my friend Sarah for helping me to make headway.

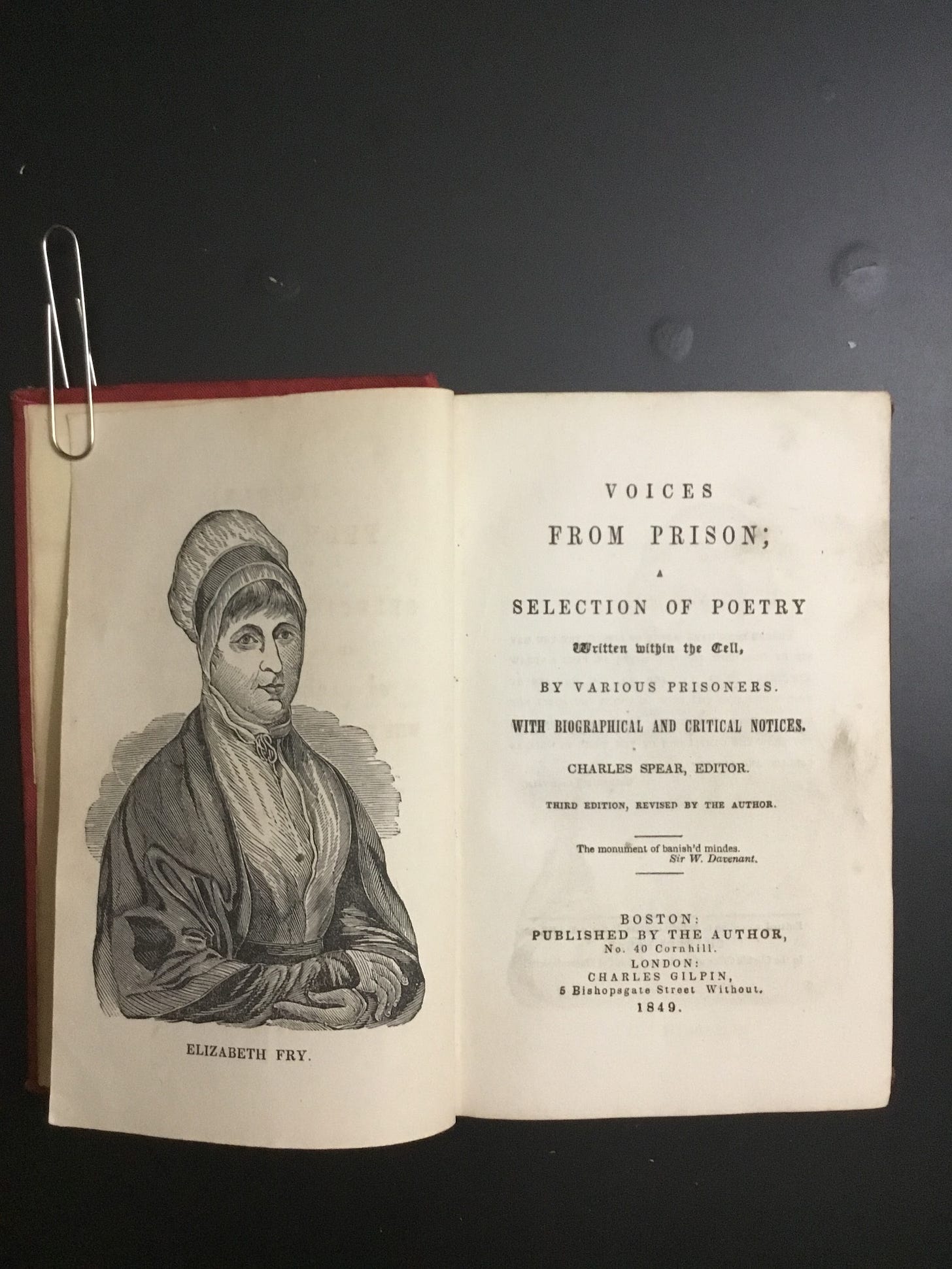

For years, I’ve wanted to acquire a first edition of John Murray Spear’s Voices from Prison: A Selection of Poetry from Various Prisoners, Written within the Cell for my collection. Voices is said to be the first anthology of American prisoners’ poetry. I haven’t found a first edition yet but I do have a third edition printed in 1849.

Spear compiled and self-published the book in 1847. It includes prison poems by abolitionist political prisoners like William Lloyd Garrison and Placido, the Afro-Cuban poet executed for inciting a slave revolt, along with verse from prisoners who Spear knew personally.

John Murray Spear (c.1804–1897) is a very interesting historical figure. He was a Universalist minister and a conductor on the Boston Underground Railroad. He was also a pioneering opponent of prisons and imprisonment, rejecting the prison reform movement and embracing arguments that anticipated those of more contemporary prison abolitionists.

Prior to the Civil War, some antislavery abolitionists were involved in prison reform movements that supported solitary confinement or rigorous work requirements to supposedly reform prisoners. However, other abolitionists saw a connection between the injustices in new prison institutions and the prison-like conditions faced by enslaved people on plantations.

Many fugitives from slavery, including Frederick Douglass, had spent time in brutal southern prisons where corporal punishment was common; so had abolitionists who aided self-emancipated Black people. They saw parallels with northern prisons as well; Douglass wrote an editorial exposing the use of waterboarding in New York’s Sing Sing, and many abolitionists, including William Lloyd Garrison, were horrified by the use of capital punishment. They also pointed out that many prisons disproportionately incarcerated free Black people, supplementing and reinforcing the racist regime of slavery in both the North and South.

Spear was imprisoned himself for helping an enslaved woman escape in 1841. The experience further radicalized him, and he became an ardent opponent of prisons, in the North and the South. He rejected the reformist stance of mainstream anti-prison societies and deliberately chose independent action instead, declaring that he was “a limb of no philanthropic machine.”

Spear’s independent initiatives were focused on directly aiding prisoners and on amplifying their voices. Along with his brother, Charles Spear, he helped found and co-edit a journal titled The Prisoner’s Friend. From 1845 to 1847, The Prisoner’s Friend ran articles denouncing capital punishment and the racism, violence, and injustice of the carceral system. The journal was not just for those on the outside; the Spears circulated it within prisons and formerly incarcerated people frequently wrote articles in its pages.

John Murray Spear also worked to provide direct support for prisoners. He donated some 7,500 books to prisons. He wrote letters and offered food, fuel, and advice to over 800 incarcerated people. In Boston, he worked with indigent formerly incarcerated people, trying to help them find jobs and community and to avoid rearrest. He wrote tracts in which he denounced plantations, factories, patriarchal families, and prisons as parallel institutions of oppression. Of the last in particular, he wrote that it was his goal “to abolish those wretched buildings.” If you’re interested in learning more about the anti-prison work that 19th-century abolitionists did, I recommend reading some of Jesse Olsavsky’s scholarship.

In his later years, Spear became obsessed with the construction of a “new motor”—an electro-spiritual machine that was supposed to be filled with holy life and function as a Messiah. Even more controversially, he advocated for free love, birth control, and women’s rights to refuse sexual intercourse in marriage. He had an extramarital affair with women's rights advocate Caroline Hinckley which led to the birth of a child in 1859. This further estranged Spear from his former networks and contributed to his quiet erasure from abolitionist memory. He remains, however, a pioneering figure who saw that prison, like chattel slavery, was incompatible with justice and freedom.

Who’s going to make the feature-length movie about John Spear’s life?

Publishing

Haymarket is releasing a Spanish edition of We Do This Til We Free Us in November! Lo que haremos hasta que nos liberemos is available for preorder now.

Podcast

This episode of Into America profiles the incredible work of Miami’s Freedom House Mobile Crisis Unit, a 911-alternative response team for mental health emergencies. The podcast follows the team spearheaded by Dream Defenders as they provide different components of holistic, community-rooted care to residents of Miami’s mostly Black Liberty City neighborhood. I think it’s impossible to listen to this episode and not feel hope. The previous episode of Into America gives the backstory of the mobile unit’s name, which honors an innovative and hugely impactful Black medic corps in 1960s and 70s Philadelphia.

Prose

I’ve read two long pieces this month that have stuck with me…

Writing in the UCLA Law Review, Naomi Murakawa breaks down the mechanisms through which reformist politics have co-opted elements of the Movement for Black Lives and used them to reinforce policing and resist radical change. Murakawa describes this dynamic as “repression through a politics of recognition” and traces the ways it has taken hold since the murder of George Floyd.

The other piece I’ve been thinking about a lot is Roxanna Asgarian’s thoughtful and comprehensive call for the abolition of family policing in October’s In These Times. She makes the case so clearly, and gives background on the movement’s relationship to the social work profession and the larger policing abolition movement.

Poem

This poem by Cyrėe Jarelle Johnson speaks to me because it captures both the richness of grief and the persistence of hope, and honors the link between them.

Yes, grief is a sored horse that bucks and hurts,

yet we tug the reins and survive the worst.

Potpourri

This week will kick off the first-ever Banned Books in Prison Week. Join PEN America as they release their new report on the topic on October 26.

It’s my birthday month (October 19 is the actual day) and as always I would love it if everyone who wants to can support REBUILD to celebrate with me.

I’m organizing a free store for winter items for newly arrived asylum seekers and migrants on November 18. We welcome donated items and volunteer help..

My friend and collaborator Andrea Ritchie’s new book Practicing New Worlds: Abolition and Emergent Strategy is out TODAY. It’s an essential resource for organizers, and I think others who are curious about emergent strategy will get something valuable out of it, too.

I’ve been a fan of Jen Cloher’s music for years, so imagine my surprise and delight to finally listen to the album they released earlier this year and to hear “Protest Song.” I had to listen to it four times to make sure I was hearing the lyrics correctly, LOL.

“Hope is just a discipline/Every day I start again/With a broken heart open.”

WUT???? So of course, I scoured the web and found an article in a magazine called Big Issue Australia that offers some context for the song and the lyrics. Doug Wallen writes in a short profile of Cloher’s new album:

That idea of solidarity under dire circumstances is echoed in ‘Protest Song’, which questions the impact of a protest song but highlights its undeniable power of hope. It was inspired in part by friends of Cloher’s who attend marches and activist events but sometimes doubt their impact—one admitted that they attend simply so that others will feel less alone. The song’s lyrics also borrow from American activist Mariame Kaba, who advocates for dismantling the prison industrial complex and has spoken publicly about hope as a daily practice. Cloher sings, “Hope is just a discipline/Every day I start again/With a broken heart open.”

I SCREAMED! It’s an honor to be included in a small way in Cloher’s art AND the song is wonderful so it will be on repeat for years in Casa Kaba, you best believe.

I found a few other words about the inspiration and meaning of the song:

When reflecting on Protest Song, Jen mused that it was written in order to convey the closeness and connectivity between people and their own ideologies. “It is always nice to know someone is feeling the same as you,” they believe.

Let’s just say that I am killing it in 2023 with the musical shout-outs. This spring it was hip hop and also jazz-folk, then this summer it was hardcore metal and now it’s also some folk rock. No one can tell me a thing until at least 2029 🤣!!!!

I love dance and this video titled “The Evolution of Dance” lives rent-free in my head.

I’m a collector of many things including books. I love the fact that the Honey and Wax Book Collecting Prize seeks to recognize and encourage young women book collectors. They recently announced their prize winner and honorable mentions. I hope the variety of collections featured will encourage other young people to create their own book collections. You don’t have to break the bank to collect. Focus on an interest, hit up some used book stores or Ebay and you’re off to the races.

A very cool thing in Amsterdam.

Cool Library Thing of the Month

I love this story from last year about an eight-year-old who was so eager to share his book with the world, he snuck it onto the library shelves. More proof that public library employees and patrons know what’s up, and the details about the book itself and its author are great.