Welcome to my personal newsletter! In this issue, I share thoughts and resources about restorative and transformative justice. I recommend two podcast episodes and several articles I enjoyed, plug my 2024 transformative justice calendar, and more.

I want to say something more about the current genocide of the Palestinian people by Israel but I don’t have any words that I feel rise to the moment. I will lean on these words by June Jordan for now:

“In this crisis, for example, it is not okay to use my tax dollars to perpetuate the dispossession, humiliation, and wretched impoverishment of an entire people. That is not okay with me. That is not okay with more and more of us—we who have been sidelined and silenced by the White House, and inside our own homes, and face-to-face with our fears that we will be called antisemitic if we speak up. Can we stand face to face, and tell the truth to each other?”

Kameelah Janan Rasheed recently wrote that “wars and genocides are often reduced to a series of unresolved interpersonal conflicts.” I agree that this is not the correct way to understand them. They are material/political struggles of domination, control & violence. They won’t be resolved through dialogue among strangers or even in circles among people who know each other. Interpersonal conflicts and harms do exist, however, and those need resolution in order for us to move forward with the world we want to build. We need to find the ways that work for our communities to repair those harms. The rest of this newsletter focuses on some of those ways.

People who know me have heard me say many times that I see living mainly as a process of shrinking the gap between my values and my actions. There are challenges, of course, because our values are often in conflict with others’ and they are also contextual, so they are not brick walls. Still, we can try to do our best.

Some people (on the Left(s) and the Right) stay furious with me because I embrace transformative justice (TJ) as a value and practice. I believe what angers them is that they cannot bully me or force me to abandon my long-standing values. I’m committed to the practice. At the center of TJ processes is consent. No one is conscripted to take part. And there are many more people who want to take part than there are people willing to facilitate processes. I wish this wasn’t the case.

I’ve been called into dozens of TJ and community accountability (CA) processes over the years. When I have agreed to participate, it’s because I have a political commitment to addressing violence in my communities how I can. No one who I’ve ever been in process with gets paid. We facilitate within our communities. The emotional and other work is intense and can be difficult. Some processes I’ve facilitated/coordinated have met their intended goals and others have not. I think that everyone involved would attest that they all made some difference and that taking part did not harm them. I know that’s not necessarily the case for other people who have engaged in their own processes. I also know that the existing system of criminal punishment leaves many more people deeply harmed and many fewer people changed for the better. So it’s worth trying other interventions.

A few years ago, under a Facebook post about TJ and “failure” by writer and disability justice practitioner Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samaransinha, I noticed a comment by Rebel Sidney Black. Sadly, they have passed away since then. Their comment resonated, and I asked them if they would be OK with me sharing it with others as part of a workshop. They agreed, and I’ll share it here with you:

I think a lot about my own tj “failure” stories, which center the abuser and their willingness or ability to transform and ignore the community care that we pour into survivors as well. What I know is that I prayed with, held while they cried, sat beside, shared meals with, strategized alongside, and had the back of so many survivors regardless of what the person harming them decided to do. All I can offer is the willingness to work with someone who’s done harm, the willingness not to throw away BIPOC people who are fucking up, and if they don’t take that opportunity—if they throw themselves away—that’s on them, that’s not me failing. It’s such big work that I only hope to help along during my lifetime.

Many people want to talk with me about TJ/CA processes and I mostly decline. The specific stories and experiences that I’ve been privy to aren’t mine to tell. Infuriating, I know, in our current era of compulsory confession and parasocial trauma bonding. What I will say is that people who are on the outside of TJ processes often have no visibility into them unless the processes are explicitly public. That’s as it should be. Not being included in everything is fine. Some things aren’t actually our business.

I will not be regularly facilitating processes anymore because my capacity is unfortunately too limited and my involvement now also sometimes shifts dynamics in unhelpful ways. But a few weeks ago, we closed a TJ process that lasted for almost two years. As we ended our last meeting, one participant said: “I’m not the same person I was two years ago; I’m different and I’m going to live differently” [shared with permission]. We should all have an opportunity to choose to live differently, especially when we’ve caused harm.

I owe many of the skills that I bring with me to TJ processes to what I learned from restorative justice (RJ) practitioners. So I thought I’d focus a bit on RJ in this month’s newsletter. (Here’s a useful essay that explains RJ and TJ in relation to one another.)

Prisons/Policing

In late 2020, I read a New York Times story about a Chinese immigrant named Henry Yao who owned a small military surplus store in Lower Manhattan. When the COVID pandemic closed down parts of New York City in March 2020, Mr. Yao tried to keep his business alive by paying his monthly $6,500 rent thanks to a loan from his sister. Soon, however, funds were running low and Henry didn’t think his business would survive the pandemic.

Before the pandemic, Mr. Yao had had no staff and worked at his store every single day for hours. His customers loved him. The article documented how Mr. Yao showed kindness to his customers, even those who had bad intentions when they entered his store:

“Like the high schooler who, trying to impress his friends, grabbed a stool, waved it around and accidentally shattered Mr. Yao’s glass counter. Mr. Yao taped everything back together and somehow got the teen to promise to improve his grades in exchange for kung fu lessons.

And then there was Eddie Reisenbichler, a troubled boy who was home-schooled and had started to explore the neighborhood. Eddie had grown up with a father who locked him, his mother and six siblings in their apartment — the details of which would surface in a documentary one day.

At the time, Mr. Yao knew none of this. Eddie was merely the boy who waited outside the store before it opened and tried to shoplift when he thought Mr. Yao wasn’t looking.

“You’re just a kid,” is all Mr. Yao would say without anger. The boy became a young man, and the young man became a friend who never forgot the lesson.

“It really does show Henry’s sense of humanity because he didn’t know who I was or how I grew up,” said Mr. Reisenbichler, who is now 22 and works at a vintage shop. “He didn’t know a single thing about me, but he still came to me with respect.”

As Mr. Yao struggled to stay afloat, one of his customers launched a GoFundMe. People raised tens of thousands of dollars to support him, and when the store reopened, customers lined up to purchase items. They helped him keep the store open.

The world is filled with countless such stories—people like Mr. Yao, who practice restorative justice without labeling it as such.

I attended my first RJ training in 1996 and it transformed the trajectory of my life. I came to RJ before embracing abolitionist politics. In fact, I can confidently say that RJ made it possible for abolition to become legible to me.

I learned a US-based RJ perspective and practice, though it turned out that I was drawn to the framework in part because of my family history and traditions. According to Howard Zehr, a key US RJ theorist/practitioner, RJ “is a process to involve, to the extent possible, those who have a stake in a specific offense and to collectively identify and address harms, needs and obligations, in order to heal and put things as right as possible." Three essential assumptions underlie restorative justice.

When people and relationships are harmed, needs are created.

The needs created by harms lead to obligations.

The obligation is to heal and “put right” the harms; this is a just response.

I’ve had many formal and informal RJ teachers and mentors, including the amazing Ora Schub (RIP), Cheryl Graves, Jamie Williams, Oscar Reed, Fania Davis, Kay Pranis, and more. I’ve either learned directly from these people in workshops/trainings or been otherwise informed by their writing and example over the years.

One person who I’ve learned a lot from is Father Dave Kelly, who leads an organization in Back of the Yards in Chicago called Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation. He is one of the most committed and effective practitioners of restorative justice I know. It was from his example that I learned about the practice of accompaniment.

Accompaniment is a Jesuit idea, meaning to “live and walk” alongside those you serve. In a 2016 interview, Father Kelly defined accompaniment as: "walking alongside. It’s very much a Biblical kind of thing of just accompanying someone on the journey. Being there on that journey. Not necessarily that I know where we’re going, but I’m committed to you as a human being and I’m going to be there for you."

Accompaniment is a willingness to connect with others, to make them feel important and recognized, never diminished. It means being consistent, listening without judgment, and offering help without condescension. It's the ability to be both a follower and a leader when necessary. When accompanying people, the aim is to show your interest rather than to exhibit your knowledge. To accompany someone doesn’t necessarily mean that you can prevent bad things from happening to them, it’s essentially a promise that you will be present beside them when they do.

For me, at the core of RJ is an admonition to show up and to connect with someone else’s humanity. Father Kelley described an example of accompaniment In a blog post he wrote a few months ago:

“I went to court with another young man who I have known for most of his life. He was now 30 years old. He had endured a great deal…having had his bumps and bruises along the way. I got one of those early morning calls that he had been arrested. I worked to get him out of jail, and now accompanied him to court. As he stood before the judge, the state’s attorney called him a violent felon…even though he had not yet been convicted. There he was with his white dress shirt and black slacks and hair neatly tied back—another black man with dreads labeled as a felon.

As I sat there, I wanted to cry out “you don’t even know him!” They knew nothing of all that he had overcome—obstacle after obstacle. They didn’t know that he's in a strenuous program to become a lineman for the power company and just the day before sent me a picture of him on a pole with his white helmet….a sign that he had graduated to the next level. They didn’t know that he had three beautiful children and a beautiful wife. They didn’t know that he was one of the most respectful young people I know.

As I saw him stand there for all to see, dressed as he thought they wanted him to dress, I knew he felt as though he was seen as violent felon—guilty because of his blackness. I felt sick; I felt anger, I felt powerless. But I also felt the love for a young man who deserved to be loved.”

I aspire to become a better practitioner of accompaniment. The practice lessens suffering. People like Mr. Yao and Father Kelly remind us, in Dennis Brutus’s words, that “somehow tenderness survives.”

Publishing

Did you know that there was a riot at the United Nations in 1961? If you answered “no,” you’re not alone. I learned about this incident as a teenager from my father who worked at the UN for many years. The incident has stayed with me and I wanted to create a zine to share some of the story.

I am excited to share A Riot at the United Nations: Black Power Internationalism, a zine written by me and illustrated by Sam Modder about what happened at the UN on February 15, 1961. The incident involved many people whose names may be familiar, including Maya Angelou, Mae Mallory, Leroi Jones (later Amiri Baraka), Abbey Lincoln, and many more…

You can purchase a copy of the zine here in December.

The Spanish edition of We Do This Til We Free Us is now available and so is a French edition! It’s really incredible to me.

Prose

Some recent TJ/RJ related essays I’ve read…

This wide-ranging conversation between Bench Ansfield, Dean Spade, and Rachel Herzing about abolitionist infrastructures asks what we need to build to help transformative justice flourish.

This Chalkbeat article looks at the way some Chicago public schools have successfully implemented RJ conflict-resolution practices. I was deeply engaged in this work with others while I lived in Chicago.

Family relationships are central to this compelling account of what might be the one of the few RJ processes used for a homicide in the US criminal punishment system.

This op-ed chronicles some of the participants, processes, and impacts of a Massachusetts-based RJ program called RISE (Repair, Invest, Succeed, and Emerge).

Podcast

I found this conversation with Claire Dederer about her new book “Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma” interesting. It resonated because I’ve been in discussion with others over the past few months about abolitionist values/principles for engaging with the intellectual and cultural production of people who have caused grievous harm (and been criminalized for it). The conversations have been generative and I am looking forward to continuing them with a larger number of people in 2024. I’m not sure what will come of our discussions but I will share some key learnings in the coming months.

I also recommend this podcast interview from a year ago with my friend Danielle Sered where she discusses the work of Common Justice. She lays out with such clarity and compassion how RJ serves survivors of violence, people responsible for violence, and the wider community.

Poem

I love The Seven of Pentacles by Marge Piercy and the way it calls us to nurturing and wildness and aliveness. I think it speaks to the work of RJ and TJ, among so many other necessary and generative parts of living.

“Weave real connections, create real nodes, build real houses.

Live a life you can endure: Make love that is loving.

Keep tangling and interweaving and taking more in,

a thicket and bramble wilderness to the outside but to us

interconnected with rabbit runs and burrows and lairs.”

Potpourri

A new transformative justice calendar – I made a 2024 transformative justice calendar with art from my comrade and friend Olly Costello and designed by Cindy Lau. Preorder a copy or 10. They make beautiful gifts to yourself and your communities for the holidays or just because. All proceeds support the work of REBUILD. Preorder the calendar by November 24 and preview the full calendar here.

My comrade Jeri was recently released from prison and is in an abusive living situation. If you have a few dollars and can contribute to helping him afford a new space, please do so here.

I really appreciate these two restorative justice–focused videos from Common Justice: Donnell’s Ever After: and Doing Sorry.

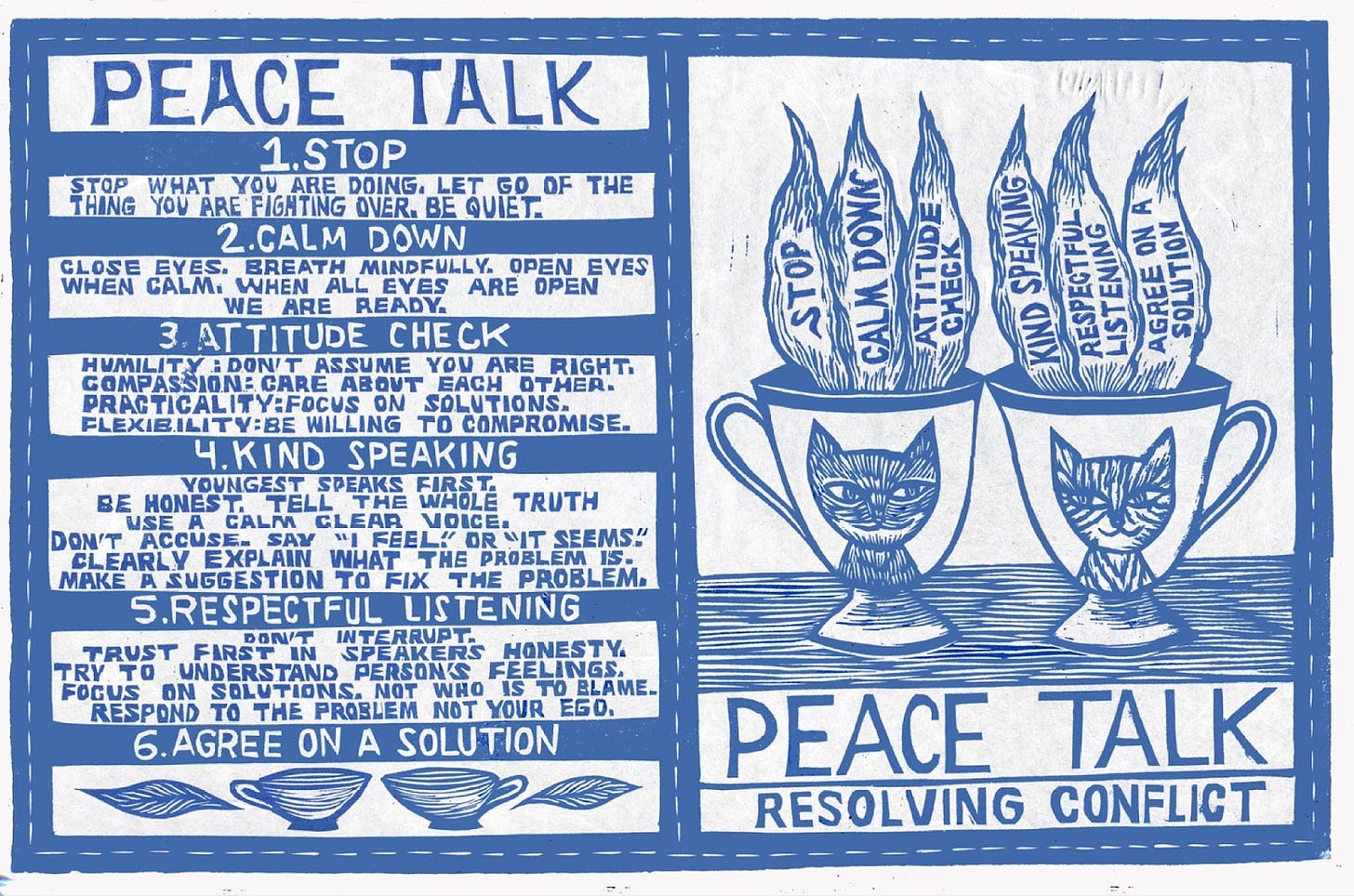

I saw this poster by Meredith Stern on the Justseeds site. It’s free to download and I think would be excellent to put up in homes, classrooms, and in various community spaces.

This song—”Jailer” by Asa—came out a few years ago and I still listen to it regularly.

I recommend this resource and workshop by my friend nuri nusrat focused on having restorative conversations, as well as this resource and workshop by my friend Jenny Viets on facilitating restorative justice circles at home.

A few years ago, I asked some artist friends to contribute to a restorative justice poster project.

You know that I love zine. Go visit this new exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum: Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines.

I read this collection of testimonies from Gaza and found it profoundly moving: “Can You Tell Us Why This Is Happening?”

A new pocket zine for youth about de-escalation is coming soon.

Cool Library Thing(s) of the Month

Watch this video about my young comrade Pepper, who supported her public library by participating in For the People’s Libraries & Lemonade project this summer. Watch till the end to confirm what good taste she has LOL.

I got to talk public libraries with the terrific Melissa Gira Grant on one of my favorite podcasts, Death Panel. You can listen here.