“Tear Down the Walls”: The 1972 Berkeley Prison Action Conference

Or How We Still Need Abolitionist Conferences & Gatherings in the 21st Century

I have some documents from the 1972 Struggle Inside conference in my personal collection. They include a report about the conference written by Karlene Clouse and some conference agendas, among other documents. I was reflecting recently on how important conferences have been for abolitionist visioning and organizing over the past 30 years. And these days, it’s harder than ever to convene such gatherings. The COVID pandemic made it difficult for us to safely bring large groups together. But even before 2020, conferences had become cost prohibitive, and people are less willing to pay to attend them. Many people also feel that the labor to organize gatherings is thankless and fraught, and they are correct in important ways.

Yet, conferences and convergences have historically strengthened our organizing efforts. I met and developed relationships with some of my most trusted comrades at various conferences over the years. The Right-wing understands the value of such opportunities to gather and their supporters fund countless conferences and convergences. We on the Lefts seem to have become more ambivalent about the value of conferences, hence making it more difficult to strategize across various silos of work.

A couple of years ago, abolitionist organizer Micah Herskind crowdsourced a useful compilation of abolitionist conferences and convergences. The list begins with the 1972 Struggle Inside conference.

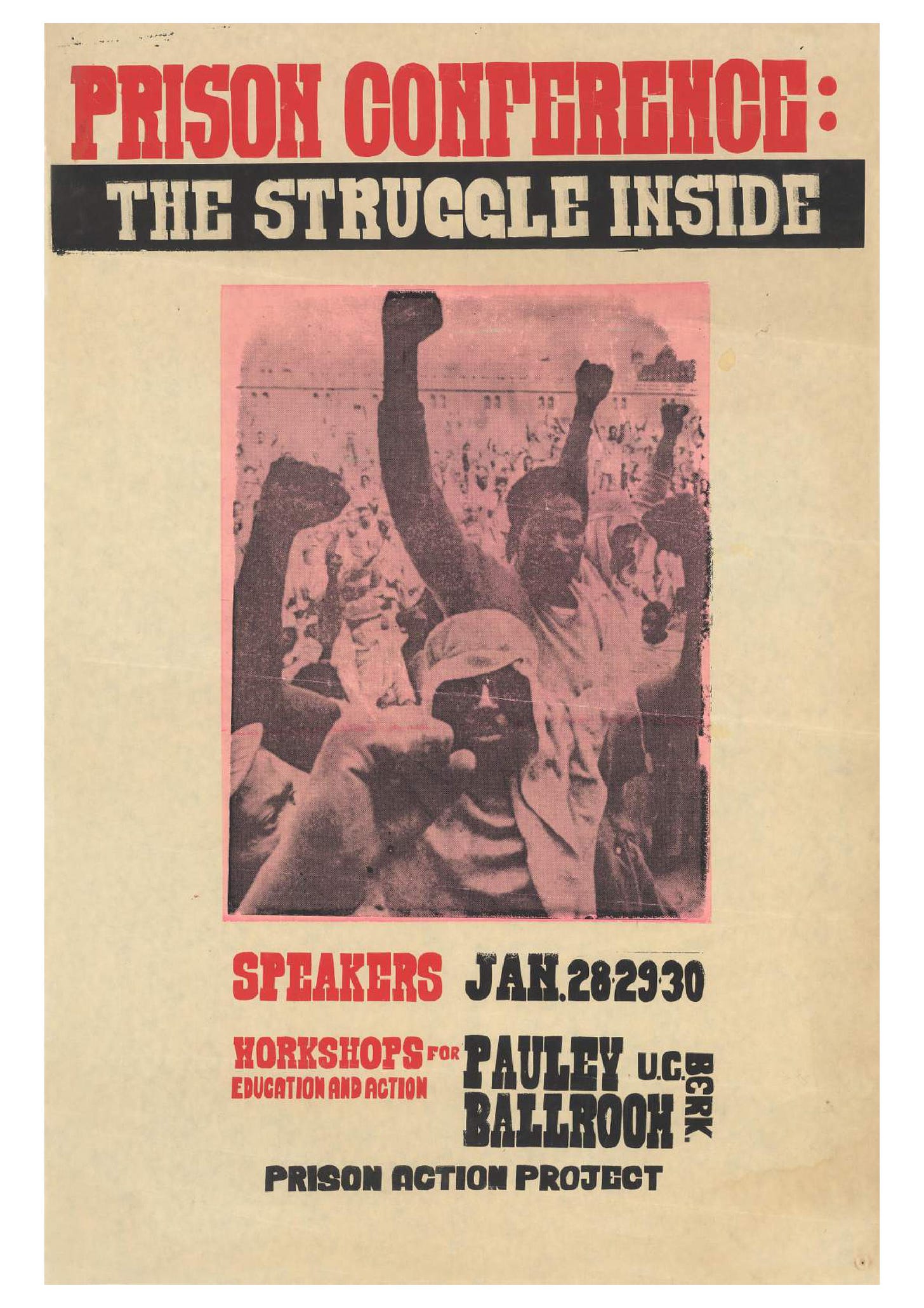

The January 1972 Prison Action Conference “The Struggle Inside” at UC Berkeley was a key moment in the modern prison abolition movement. The conference drew inspiration in part from the August 1971 killing of George Jackson, a prisoner and radical intellectual who California correctional officers murdered. Jackson’s death led to a sense of urgency among activists inside and outside prison. The arrest of scholar and activist Angela Davis, accused of purchasing some weapons used by Jonathan Jackson (George’s brother) in an unsuccessful attempt to free prisoners and take hostages in a courtroom in August 1970, intensified this sense of urgency. George Jackson’s death and Davis’ trial led to a broad push to educate the public and to motivate people to question and mobilize against prisons.

Berkeley’s School of Criminology, which had become a center of radical scholarship opposing the carceral state in the late 1960s, partnered with community members to organize the Prison Action Conference. Faculty members Tony Platt and Herman Schwendinger led the school in critiquing justifications for prison and policing, and in advocating for policies such as community control of police and support for prisoner solidarity.

The conference reflected these priorities. According to an official summary released by the conference, the 600 attendees included not only attorneys, doctors, and criminologists, but several formerly incarcerated men and women who discussed prison conditions and the justice system. The conference’s slogan was “Tear Down the Walls.” As a Statement of Principles explained, “Tear Down the Walls” referred both to the desire to “abolish the prison system completely” and to destroy “the walls in the outside society that keep men and women chained to a meaningless life in an inequitable social system.”

Activists wanted to push for immediate changes to help prisoners and through the showing of the film Angela: Portrait of a Revolutionary, the conference encouraged attendees to contribute funds for Angela Davis’ defense. Other actions included a march on Sacramento to protest the construction of two new maximum-security prisons and a demand that California prisons provide a fully staffed legal center for prisoners in every facility.

Organizers also, though, hoped to create and disseminate a broader critique of the prison and of the social system that made prison possible and necessary. Karen Wald, a journalist and anti-prison activist who had interviewed George Jackson and helped organize the conference, explained to a television interviewer that, “People who are filling the prisons in this country are there basically because they’re poor…within that category of poor people, most of them are non-white.” Wald suggested that to transform prisons, society needed to end conditions which led people to desperation, poverty, theft, and drug use.

Workshops focused on opposition to experiments on prisoners, improved medical care, and sentencing reform. Conference members also discussed how to build connections between prisoners and community groups outside prisons, and the links between incarceration, racism, and poverty.

The conference specifically highlighted the injustice of the Adult Authority Board in charge of parole, whose decisions were hasty and arbitrary; the board invariably refused parole to prisoners with left or radical political commitments. Presentations also discussed the prison “slave labor” system; prison workers received as little as 3 cents an hour, and prison job training programs were condemned as inadequate and obsolete. A panel of formerly incarcerated women advocated for the creation of a work-furlough program for women, and debated whether organizers should focus on the immediate needs of reform in women in prison or should focus on longer range and more revolutionary approaches.

The highest profile speaker at the conference was Black Panther and activist Afeni Shakur. Authorities had arrested her on charges of conspiring to attack police stations along with 20 other defendants. Her spectacular defense of herself in court was key to the group’s acquittal in 1971.

The lineup included other speakers such as Berkeley attorney Fay Stender, former prisoner and Black radical workers organizer Don Williams, and Frank Rundle, the former chief psychiatrist at Soledad Prison, where Jackson had been incarcerated. Rundle lost his job after five months as the sole psychiatrist in the prison because he refused to hand over confidential prisoner psychological records to authorities. In his talk, he excoriated Soledad prison for soliciting false psychological reports used to deny prisoner’s parole, for using shock treatments as punishment and to subdue prisoners, and for routinely withholding necessary pain medications and other vital medical treatments.

The criminology school’s criticism of the justice system incensed police departments and conservative Republican California Governor Ronald Reagan, and bowing to political pressure, Berkeley closed the school in 1976. Berkeley’s radical scholars, however, remained influential, founding the long-lived Crime and Social Justice journal and publishing pioneering anthologies like The Iron Fist and the Velvet Glove: An Analysis of the U.S. Police (1975).

The Prison Action Conference itself took the lead in advocating for an abolitionist approach to prisons, and warning about the limits and dangers of reform. Its Statement of Principles argued, “We must guard against the danger of lending ourselves to the development of new forms of control under the guise of reform which make the prison a more effective tool of pacification.” These warnings, themes, and strategies would become vital touchstones for resistance during the massive carceral boom of the next decades.

NOTE: I am not sure how many people actually click on the links I share to the archival documents that I share in this newsletter. Do you find the documents of interest? Let me know in the comments as this helps me to refine what I share.

Sources Consulted

Dan Berger, Captive Nation : Black Prison Organizing in the Civil Rights Era, University of North Carolina Press, 2014, pp. 169-171.

Karlene Clouse, “The Struggle Inside : Summary of Conference,” 1972.

Josh Hardman, “UC Berkeley: The Closure of the School of Criminology, 1976,” The San Francisco Digital History Archive, 2016.

“Prison Action Conference at UC Berkeley,” Bay Area Television Archive. Accessed May 13, 2024.

Tashan Reed, “Afeni Shakur Took on the State and Won,” Jacobin, November 18, 2021.

Antonio Mejías-Rentas, “How Angela Davis Ended Up on the FBI’s Most Wanted List,” History.com, January 25, 2023.

“Statement of Principles: Prison Action Conference. "The Struggle Inside." Berkeley, January 28-30, 1972.

“The Struggle Inside: Prison Action Conference Schedule,” 1972.

i love checking out the links + sources. very helpful!

I like that you link to archival documents.