In September, I attended the Through the Portal conference in Chicago. As part of the conference, there were a few Sunday afternoon conversation spaces. These “incubator sessions” focused on specific topics, including one about movement building and coalition work that I had the privilege to co-organize and co-facilitate with some terrific comrades. We opened up the conversation by focusing on grief. This was the section that I facilitated. We asked: 1) Where are you putting your grief or frustration? 2) Do you have a practice for expressing or releasing these emotions? If not, where are those feelings going? How are they manifesting?

In pairs, participants shared their responses. It was a good way to open. I also read these words from Sarah Jaffe’s new book From the Ashes: Grief and Revolution in a World on Fire out loud:

“Grief is excessive; so is revolution. It is a defiant ‘yes’ when the rest of the world would say no. It is a refusal of the foreclosing of our time, an overflowing of humanity into the places that it is forbidden. We will not be machines anymore." These words are also available as a print from Radical Emprints.

In Let This Radicalize You, Kelly Hayes and I include a chapter titled “Hope and Grief Can Co-Exist.” Something that both Kelly and I have been remarking on regarding our communities in the past few years—certainly through these pandemic years—is the amount of unprocessed grief that our people are holding. I’ve heard it said that “you don’t move on from grief, you go on and carry it with you.” That resonates with my experience of grief. This year I have been leaning into Chera Hammons’s words:

Even when you think

you can’t go on,

the day carries you.

If you are currently trying to process grief, I hope that “the day carries you.”

In this month’s edition of Prisons, Prose & Protest, I share some thoughts about Freeman’s Challenge, a book by Robin Bernstein. I recommend a podcast, several good recent articles, and much more…

I am deeply honored to receive the 2024 Mujahid Farid Award from my comrades at Release Aging People in Prison. You can read more about Mujahid here to get a sense of how meaningful it is to me to receive an award named after him. If you’ll be in NYC on December 2, please come celebrate with me. If you can’t make it, please consider supporting RAPP’s life-affirming work.

If you appreciate this newsletter, please share it with others, and importantly please click the heart icon so that more people can find it.

Prisons/Policing

Some critics of prison and the carceral system argue that mass incarceration is an extension of chattel slavery. The Thirteenth Amendment, which formally freed enslaved people, includes a carve out which allows for involuntary servitude “as punishment for a crime.” Slavery, in this interpretation, moved off the plantations and set up shop behind prison walls to continue to exploit the labor of Black people, especially in the South.

Robin Bernstein’s new monograph, Freeman’s Challenge: The Murder That Shook America’s Original Prison for Profit, substantially challenges this argument of seamless continuity. Auburn State Prison in upstate New York is the focus of the book. Auburn and its namesake, the Auburn System, established a carceral structure for profit in the North in the 1820s, well before slavery ended in the United States.

The engineers of the Auburn System, unlike religious reformers in neighboring Pennsylvania, were not interested in saving souls or in penance. Instead, Bernstein writes, “They viewed a prison as a vehicle by which to soak up state funds, build banking, stimulate commerce, manufacture goods, and develop land and waterways.” Committing a crime stripped people of any “inherent right to benefit from their labor—vocationally, morally, or otherwise.” Prisoners labored in total silence and could not even look at each other. If they did, the guards would torture them either by whipping or by subjecting them to the shower-bath, a form of waterboarding. (I wrote about these tortures several years ago on my blog).

Prisoners made items for sale, from hardware to silk. But Bernstein also emphasizes that the prison became enmeshed in a web of capitalist arrangements that were not easily reduced to labor exploitation. Building the prison itself attracted capital and workers to Auburn. The prison system was a major tourist attraction; people paid to watch prisoners work in silence. Prisoners’ corpses helped train doctors at a nearby medical school. Prison administration positions were plum political patronage. Everyone, Bernstein shows, had an interest in the prison.

The Auburn System had a complicated relationship with racism, which was mostly invisible to contemporaries. The Auburn System disproportionately incarcerated Black people, but their overall numbers in Auburn were small, and the prison did not hold many people by our present-day standards. As a result, most people who lived in Auburn in the 1830s and 40s did not necessarily connect Blackness with criminality.

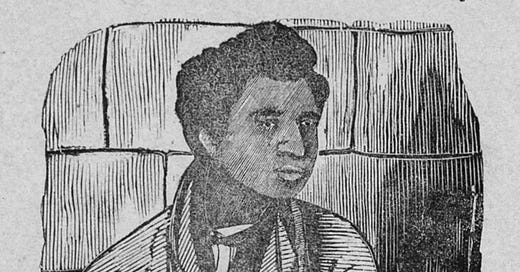

Those racist links were forged when William Freeman, a 22-year-old Black and Native American former prisoner, murdered four white people, including a child, in 1846. Freeman had been imprisoned in Auburn in 1840 for stealing a horse. He was 15 years old when he was sentenced to hard labor. He insisted that he was wrongfully accused and never stole anything. While incarcerated, he worked 12 hours a day without compensation. The jailers beat him for refusing to work and he suffered hearing loss and brain damage. Upon his release, he tried to get payment for the work he had done. When legal channels failed, he bought knives and murdered the white family in apparent retaliation against the town which had robbed him of his years and of compensation.

The infamous, closely followed trial was a rehearsal for racist discourses around mass incarceration that persist to this day. The prosecution insisted that Freeman was an exemplar of innate Black criminality. The defense agreed that Freeman was, in fact, debased, but argued that this was because white people had not taken their proper role of moral leadership by, for example, investing in Black schools. These arguments represented a broad, relatively new consensus linking Black people, crime, and violence. Both sides also framed the prison as a way to police, punish, and reform Black populations.

William Freeman said again and again that the carceral system was a unique and unbearable injustice. The people of Auburn—hard-liners and reformists, Black and white—were unable and uninterested in hearing that critique, in part because the prison was so intertwined with their lives and livelihood. The critique is still difficult for most people to hear today, which is in part why some prison reformers have compared prison to slavery, a much more universally condemned institution.

Bernstein, though, shows how prison, while parallel and related to slavery in some ways, has its own unique history and its own unique relationship to capitalism, violence, and white supremacy. Freeman’s Challenge is a meticulously researched, imaginative, and convincing argument that we need to understand that history and those relationships if we hope to create a better, prisonless future.

Note: Today, prisoners at Auburn “make every New York State license plate—2.5 million pairs annually.” While Freeman was not paid for his labor, prisoners at Auburn currently make a negligible 65 cents an hour.

If you purchase the book through the University of Chicago Press, you can use code BERNSTEIN30 for a 30% discount.

Publishing

The inaugural 2025 Sojourners for Justice Press Wall Calendar is now available for preorder! Calendars will ship in early December. Preview the calendar here! Preorders end November 16 and this is the only way to get a copy of the calendar this year.

Sales directly support the operations of Sojourners for Justice Press. Every calendar purchase keeps our press running by covering costs associated with paying staff, authors, designers, and editors, in addition to printing, mailing, distribution, and more.

Filled with significant dates from feminism and publishing in radical Black history, the SJP 2025 calendar features historical figures and groups including Ida B. Wells, Harriet Tubman, Lucy Parsons, the Black Panther Party, MOVE, Assata Shakur, Abbey Lincoln, Fannie Lou Hamer, Louise Thompson Patterson, and more.

Conceived by Mariame Kaba. Designed by Cindy Lau and Neta Bomani. Published by Sojourners for Justice Press in 2024.

Offset printed, saddle stitched, 12 by 12 inches.

Prose

Read this narrative of a life lived under siege in Gaza and of the pain of displacement, by Alia Khaled Madi.

I really appreciated this essay about the violent suppression of the University of Virginia’s Gaza solidarity encampment written by Levi Vonk, a UVA professor. It’s part of a series on last spring’s student encampment movement published in October by Public Books.

In this Hammer and Hope essay, Rachel Herzing, Amelia Kirby, and Jack Norton offer an excellent analysis of the way the prison industrial complex supports and contributes to ascendant fascism in the US.

I am grateful to everyone plotting out organizing plans for different election-outcome scenarios; in this essay for Inquest, Silky Shah offers a clear-eyed run-down of where organizing to protect immigrants stands currently, and of where it will need to go depending on Tuesday’s outcome.

Kim Kelly writes about the impact of climate catastrophe on incarcerated people and about the unconscionable failure to evacuate prisons and jails in the path of Hurricanes Helene and Milton.

This blog post by Marion Teniade gets to the heart of climate solidarity. “Connection is the only way to get us through the peril. Community is the only place I can put my hope and imagination for something better.”

My friend, comrade, and coauthor Kelly Hayes writes one of the best newsletters around. This interview with Meghan Daniel, director of services for the Chicago Abortion Fund, about the current crisis in financing faced by US abortion funds, is excellent.

I love reading about the steps people take to intentionally build community in their neighborhoods. There are three case studies here, as well as some resources for those interested in making similar connections where they live.

I appreciated this essay by Selome Hailu about her experience attending the San Quentin Film Festival, the first-ever film festival held inside a prison.

The news from the ongoing Sudan genocide is chilling; reports this week of atrocities in villages south of Khartoum illustrate the horrors to which civilians are subjected.

Podcast

I talked in my mid-October newsletter about some incredible wins over the last decade+ in organizing against youth incarceration in Illinois. This three-part series about the successful campaign to close St. Louis’s notorious Workhouse jail does a great job of exploring another important abolitionist win. For the In the Mix podcast, Ashley C. Ford talks to the organizers—many of whom entered the fight with lived experience of the Workhouse’s horrors—who made the closure happen.

Poem

“Wildflowers” by Maya Stein asks the right questions in this time of deep grief.

Projects for Your Year-End Donations

I am making year-end contributions to each of these. Please join me.

REBUILD - Funds are urgently needed to keep this program going in 2025. We need to raise $100,000 by December 31. I have committed to match up to $10,000 in contributions. Additionally, donations of $50 and more are eligible to enter this raffle by November 30.

Prison Library Support Network - PLSN is pooling $15,000 to keep its reference-by-mail project alive. Since 2021, they’ve answered 3,000+ research questions from people in jails and prisons—entirely as volunteers. If you donate $1 by 12/31, it will be matched by $5 up to $15,000—that's potentially over $90,000 toward helping people in prisons access information they need on their own terms.

My comrade, imprisoned intellectual and organizer Stevie Wilson, is raising funds for an inside study and mutual aid group. Please consider supporting them here.

The Sameer Project - This is a mutual aid project for Gaza led by Palestinians.

BX Rebirth - Please make a note that you are donating to the MK Birth Liberation Fund if you donate.

Palmetto State Abortion Fund - I am a monthly contributor and they are doing essential and needed work. Your donations get put to immediate use to support access to abortion. In October, they helped 200 people; up from 170 in September.

Potpourri

Save the Date—Black Zine Fair is back on May 3, 2025!!

I’m very excited about the first two recipients of the Audre Lorde Scholarship that I endowed at Pratt Institute where I received my MSLIS a couple of years ago:

Celebrate the Chicago release of We Grow the World Together: Parenting Towards Abolition at Haymarket House on November 18.

Flashlights—“A first of its kind digital archive that introduces the world to jailhouse lawyers through a powerful collection of letters, poems and art created by [the Jailhouse Lawyer Initiative]’s jailhouse lawyer members.”

Transformations (Midwest, Ozark, NW Arkansas), just launched A Path of Roses, a digital sex workers field guide and media toolkit campaign to connect and support young girls, trans women of color, and sex workers.

It’s no secret how much I love tea—I was captivated to watch this craftsperson creating a teapot by hand.

Some of my zines that are usually only available in hard copies at in-person zines fairs are back in stock at Printed Matter: here, here, here, here, here, and here.

Dr. Ariana Brazier’s Imagination Playbook is a gorgeous resource of play-based activities “designed to materialize the recommendations set forth in Ruha Benjamin’s Imagination: A Manifesto.”

The Building Movement Project and SolidarityIs have created a beautiful, insightful transformative solidarity practice guide.

I love both the message and the young narrators of this short video.

When I was in Chicago a couple of months ago, I picked up this wonderful herbal infused shea butter by Sage House Apothecary at the Silver Room. I love it. Sage House Apothecary is a Chicago-based brand founded by Reiki healer Christie Edwards.

Nina Simone singing Langston Hughes.

Cool Library Thing of the Month

A long-overdue-book story that made me laugh.

Thank you. Your words are restorative.

“you don’t move on from grief, you go on and carry it with you.”