Welcome to my personal newsletter! In this issue, I share a recently acquired letter and write about its historical context. I recommend a podcast episode I enjoyed, I write about the inspiration behind Sojourners for Justice Press, I share an important Save the Date, I also share an exciting announcement and much more…

If you like the newsletter, please feel free to share it with others. Happy reading!

In peace,

Mariame

Prisons/Policing

I recently acquired a letter by the “Committee of 100” dated January 19, 1950. It caught my attention because the letter is an appeal for funds to support the defense of three Black men: Charles Greenlee, Samuel Shepherd, and Walter Irvin. The names were familiar to me because their story is powerfully recounted in a book I read many years ago by Gilbert King titled Devil in the Grove. The men were part of a group of defendants who came to be known as the “Groveland Four.”

William Allan Neilson, who was on the board of directors of the NAACP from 1930 to 1946, was a key organizer and the first chair of the Committee of 100, a group of civil rights advocates who established the Legal Defense and Education Fund (LDEF) of the NAACP in 1943 and continued to solicit financial support for it.

Reading the letter, you might recognize the names of other members of the Committee including A. Philip Randolph, Tallulah Bankhead, Charles H. Houston, Alain Locke, and other luminaries.

As you evaluate the letter as a primary source document, I invite you to think as an archivist would. How would you decide whether to include this letter in a particular collection or repository?

The Groveland Four

In 1949, four young Black men were falsely accused of raping a 17-year-old white teenager named Norma Padgett.

Norma Lee Padgett got on the witness stand and pointed her finger at the three young black men seated across from her:

“…the nigger Shepherd, the nigger Irvin…the nigger Greenlee.”

Padgett was accusing these young men of raping her. With her words, she set in motion a massive injustice that would bring Thurgood Marshall to the small Florida town of Groveland in 1949.

Marshall braved constant death threats and his own personal demons to see “justice done” in the case of the “Groveland Boys.” Local NAACP organizers Harry T. and Harriette Moore would lose their lives in a KKK bombing on Christmas Day in 1951 in large part because of their advocacy in the Groveland Four case.

Padgett accused Ernest Thomas, Charles Greenlee, Samuel Shepherd, and Walter Irvin of raping her after a dance that she had attended with her husband. Two of the suspects—Shepherd and Irvin, who were both war veterans—had in fact briefly come upon Norma and her husband Willie Padgett on the side of the road where their car had broken down. They had had an altercation with Willie, who had disrespected them after they had offered their assistance and were unable to get the car moving again. The other two accused men—Thomas and Greenlee—had never met the Padgetts and in fact were not even in the vicinity at the time of the alleged rape.

Nothing about the story that Norma Padgett told added up. One of the first people she spoke with in the early morning was not told that she was raped by four Black men. She was seen by another witness getting out of the car of a white man on the morning after she had supposedly been raped. It was clear that her story was a preposterous and incredible one.

Sheriff Willis McCall. who is one of the most infamous cops of the Civil Rights Era, played a critical role in this story. He was a member of the Ku Klux Klan and known for his ruthless treatment of “suspects.” When Charles Greenlee, Samuel Shepherd and Walter Irvin were arrested, a lynch mob formed at the jail and demanded that they be handed over in order for the mob to administer “justice.” Ernest Thomas, the fourth suspect, fled the county but was found by a posse in nearby swamps; he was shot and killed on sight.

Sheriff McCall garnered a lot of positive national attention when he refused to hand Greenlee, Shepherd, and Irvin over to the mob. Here’s how Time magazine described the events in August 1949:

Sullen, glint-eyed men collected in murmuring knots in the dusty, farm-town streets. Soon, the small angry knots had become one 125-man mob pulling up at the Tavares courthouse in a 20-car caravan. Most of the mob stayed behind while its leaders walked up the steps to talk with big, easygoing Sheriff Willis McCall. “Willis,” said one,”we want them niggers.”

The sheriff let himself down on the steps and talked softly. “You know that when you elected me, I was sworn to uphold the law,” he said. “And I have to protect my prisoners.” Anyway, he added, the prisoners had been rushed off to another jail for safekeeping. (A third suspect was in the jail at the time, but was sneaked off later.)

Grumbling, the mob rode off, and almost broke up. Just for the hell of it, though, in the little farming town of Groveland, 65 miles from Tampa and not far from Willie and Norma Padgett’s house, the men with shotguns pumped 15 loads of buckshot into a Negro-owned juke joint. Then they looked around for more Negroes—but the 400 residents of Groveland’s Negro district had been carted to safety by white citizens who feared what was coming.

Calm, determined Sheriff McCall put in a hurry call to Governor Fuller Warren that brought 78 National Guardsmen to the scene. Off and on for three days, small mobs, sprinkled now with strangers from other counties, cruised menacingly in cars, or shuffled through the small-town streets, but did no damage. Then, all of a sudden, they were roused again. A hundred shouting whites with rifles and pistols roared into tiny Mascotte in trucks, forced Guardsmen and police to withdraw and took over the community for the night.

At Stuckey’s Still, a bedraggled Negro home site three miles from Groveland, the band poured shots into one house (someone thought it belonged to the father of one of the rape suspects) and started after more. Sheriff’s men and highway police stopped them with tear-gas grenades. A few miles away, whites tossing kerosene-filled bottles burned three Negro homes to the ground.

What Time magazine didn’t report and perhaps didn’t know was that McCall’s deputies severely beat and tortured the surviving three alleged suspects in the jail basement for several hours. Shepherd and Irvin confessed in order to stop the beatings. The cops encouraged the terrorizing of Black community residents by the KKK. They fabricated and planted evidence to frame the young men. Sheriff McCall was actually a racist sadist.

There was a quick trial that resulted in a guilty verdict for all three surviving defendants. Shepherd and Irvin were sentenced to death and Greenlee to life in prison. Thurgood Marshall appealed the initial guilty verdict for Shepherd and Irvin all the way to the Supreme Court, which overturned the convictions and ordered a retrial in its 1951 Shepherd v. Florida ruling.

Yet there was no happily-ever-after in this story. Driving Shepherd and Irvin back to the prison after the Supreme Court verdict, McCall and his deputy shot both men right outside of town. Shepherd died instantly. Irvin survived to testify against McCall. McCall was cleared of wrongdoing and continued to pursue and harass Irvin even after the Florida governor commuted his death sentence in 1955; Irvin was paroled in 1968 and died the next year. McCall served as sheriff until 1972.

The FBI eventually unsealed the files from the case. A major revelation was that a doctor who examined Norma Padgett found no signs of sexual assault. The new details about the case prompted the families of three of the four men who were falsely accused to ask the state of Florida to exonerate them and to apologize.

In 2020, the four men were in fact exonerated, having been officially pardoned in 2019.

Publishing

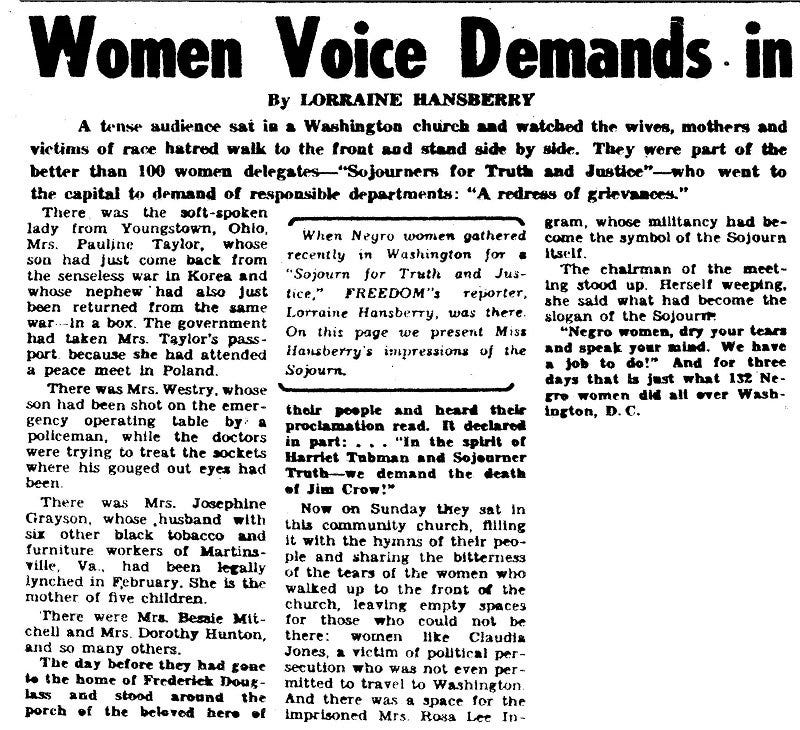

I launched Sojourners for Justice Press (SJP) in 2020. In 2021, I invited Neta Bomani to join me as co-director. The name of our press is inspired by the legacies of several Black feminists and their commitments to radical dissent. In 1951, a group of socialist and communist Black women formed the Sojourners for Truth and Justice, a short-lived but significant formation. Their manifesto, A Call to Negro Women, expressed their anti-imperialist, antiracist and anticapitalist values. Their ideas resonate today and our press hopes to advance them into the future.

The Call to Negro Women manifesto was written by poet and actor Beulah Richardson (later known as Beah Richards) and veteran Communist organizer and radical Louise Thompson Patterson (my favorite organizer of the 20th century). The manifesto was a response to the wave of repression that they were living under.

Made public in September 1951, the manifesto invoked the legacies of Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth. It invited “dear Negro sisters everywhere in the United States” to convene in Washington, DC, from September 29 to October 1 for a “sojourn for truth and justice.” The conveners were concerned about many issues including racial terrorism (lynchings, police violence, wrongful convictions, etc.), ending the Korean War, colonialism, South African apartheid, poverty, and more. In less than two weeks, more than 132 Black women from 15 states responded to the call.

In March 1952, Sojourners convened for the Eastern Seaboard Conference. At the gathering, Patterson, a founding member of STJ, gave a speech about the triple oppression of Black women. She had already begun writing and speaking about Black women’s super-exploitation in the mid-1930s, well before Claudia Jones published her influential essay “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman!” in 1949.

In his book Sojourning for Freedom: Black Women, American Communism, and the Making of Black Left Feminism, historian Erik S. McDuffie contends that STJ “advanced positions on race, class, and gender that were in many respects far ahead of the Communist Party, civil rights groups, and women’s clubs” (162). The Eastern Seaboard Conference was STJ’s second, and last, major gathering after its inaugural Washington, DC, convention in 1951.

In April 1952, Walter White rejected Charlotta Bass’s request for a formal aligning of the NACCP with the Sojourners, specifically around the defense campaign work to free Rosa Lee Ingram. This rejection, along with the Communist Party USA’s ambivalence toward and lack of support of the group and the general repression of the time, proved to be a death blow to the fledgling Sojourners for Truth and Justice. By the end of 1952, the group had disbanded.

Though STJ lasted for less than two years, it helped to articulate a Black Left Feminism that, in McDuffie's words, "paid special attention to the intersectional, systemic nature of African American women’s oppression and understood their struggle for dignity and freedom in global terms."

Many of the members of the Sojourners for Truth and Justice were writers and intellectuals; they included Alice Childress, Lorraine Hansberry, Claudia Jones, Charlotta Bass, Eslanda Goode Robeson, Shirley Graham Du Bois, and more. Some worked with and/or submitted their work to independent radical publications like Freedom and Freedomways. Sojourners for Justice Press endeavors to be a publishing vehicle in this lineage.

Please support the work that we are trying to do with Sojourners for Justice Press by becoming a KOFI member and by purchasing/sharing our publications. We are excited to publish more pamphlets, posters, and short works in 2024.

Podcast

I love this podcast, hosted by my friend Eve L. Ewing, about the possibilities created by Chicago’s guaranteed income pilot programs, and this particular episode made me cry. It shares the story of a young, formerly incarcerated man named Sherrif who started receiving guaranteed income while under house arrest. Sherrif speaks movingly about how the guarantee of money every month allowed him to provide for his kids and household even while so many of his movements and decisions were limited by the state. Eve does such a good job of making space for the human stories that can get lost in policy conversations around basic income, and I loved getting to know Sherrif. Listen through to the end for a shoutout to me that means so much.

Prose

People consistently ask prison industrial complex (PIC) abolitionists about how society will function without police. The reality is that people across the world are continually experimenting and trying out ways to increase safety and well-being in their communities without relying on police. As abolitionists we don’t ask, “What will we do without police,” we begin by asking, “What is safety for our communities?” Then we ask what the conditions are that will increase safety for everyone (or as many people as possible). I appreciated this essay by Katie Prout which provides yet another example of people creating safety without relying on police.

For more examples of ways that communities are increasing safety, visit One Million Experiments.

Poems

This month, I’m sharing the poem In Any Event by Dorianne Laux. It offers a grounding reflection on hope and on the beauty inherent in humanity. Like Laux, “I shall not lament / the human, not yet.”

Potpourri

Some big news from me about a scholarship that I have endowed. Read the announcement about the Audre Lorde Justice Endowed Scholarship!

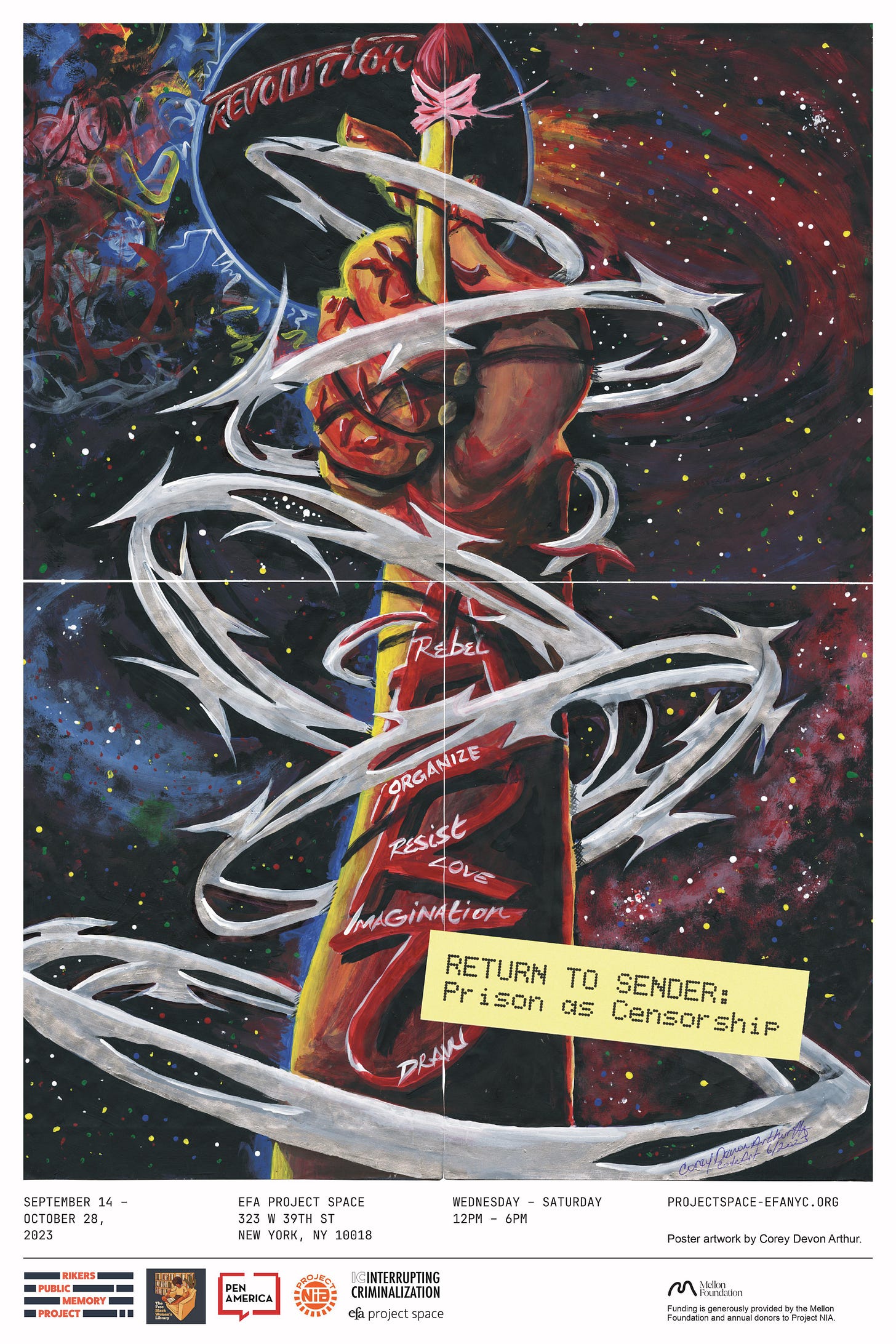

Return to Sender: Prison As Censorship - SAVE THE DATE - September 14 is the opening reception for the forthcoming exhibition that I curated, at EFA Project Space in Manhattan. RSVP here.

Update on Youth Public History Institute (YPHI) - I spent part of my summer hanging out with inspiring and brilliant young people as part of the YPHI that I co-organized and co-facilitated. Since I wrote a bit about the YPHI in a previous newsletter, I wanted to share a brief update for those who are curious. You can have a look at what we covered and discussed on the YPHI Padlet. You can read reflections about the institute in this terrific newsletter created by awesome Tia, who was our YPHI documenter. You can read some reflections from the institute coordinator Zahra here. I was exhausted after the Institute ended but I truly had a blast. Grateful to everyone who made YPHI possible and poured into it to make the experience a wonderful one.

Join our next Life Stories of Anti-Slavery Abolitionists reading group discussion on September 17. We’ll be reading about William and Ellen Craft in a new book by Ilyon Woo. Register here.

I’m raising much needed funds for incarcerated survivors. Donations are really appreciated. We still have to raise $20,000 to continue to offer commissary and care packages. You can donate directly here. If you’re in NYC, come to our vintage & handmade item sale on August 26 and 27. Help us spread the word about it too!

I recommend the film Art and Krimes by Krimes by Alysa Nahmias, which is available to watch on several streaming platforms. It tells the story of an incarcerated artist and the works he made in, and smuggled out of, the federal prison where he was caged.

Last year, my friend jackie sumell created The Abolitionist's Field Guide, a workbook that uses the stories and interrelationships of plants to explore abolitionist strategy. “Sometimes those teachings are direct perceptions, sometimes they are metaphors,” sumell writes. “Abolition, like growing a plant, requires daily attention and care.” You can purchase a copy of the workbook here.

I’m obsessed with this drink, which is basically just a souped-up bissap. Those who know, know.

If you’re in New York City, go see this exhibition at Poster House before it closes on September 10; it explores the use of imagery to create political meaning in Black Panther Party posters.

I’ve known this incredibly talented artist for many years. I love this song and more people should hear it and be aware of Tweak’G.

Cool Library Thing of the Month

Author Jorge Luis Borges was asked in 1985 to create a personal library of 100 titles. He only added 74 titles before his death in 1988. Here is the list: Jorge Luis Borges Personal Library.